When I was a kid, like any good middle child I measured my birthdays and age against that of my two brothers. Specifically against my older brother, who was born three and a half years before me. When his March 30 birthday rolled around, I know I had six months ahead where he would be four years older than me, in terms of the round yearly number we all use post-toddlerhood. Then in October, I would catch back up, and enjoy six months of being only three years his junior.

Yesterday my brother turned 50. That's a big one, and I've known it was headed my way for some time. The fact that Dwayne has hit it brings the reality of its approach home again. Right now he's four years older than me; in October, I'll close the gap again.

Another way to look at age is in terms of career. I got started pretty late, as many academics do, having taken my time wending my way through grad school. I landed my first and only university job in 1999, and I'm currently completing my thirteenth year of teaching. I'll be eligible to apply for full professor status after next year (my first couple of years of teaching were non-tenure track, so I lost a couple of rungs on the ladder). And then I'll be started the next phase of my career, probably looking around to see if my administrative experience might make me useful elsewhere, probably putting myself in position to succeed my current boss when he retires in a few years.

I've got maybe twenty years left in this business. More than I've got behind me. That's kind of the opposite of the age number staring me in the face.

This morning I ran my second 5K of 2012. I hope there will be a handful more before the year ends. When I say "ran," it's even more of an exaggeration than usual; not only was it my usual 12-minute-mile slow jog, but I also walked a lot more than I usually would find acceptable. You see, on Thursday afternoon I came down with the most sudden, violent fever I can remember. I was knitting with my students one minute, and the next I was feeling like crap and trying to get home before the shakes started in earnest. I shivered for an hour, ached for another, then took Motrin. And it was over. I waited for the next twenty-four hours for the other shoe to drop, for the gastrointestinal part of the virus to take hold or whatever, and it never did.

So I took it easy today, still cautious after that strange interlude. And I remember that even though this is the first time in my life that I've ever attempted to run 5Ks, meaning I'm about as healthy as I've ever been, I'm not getting any younger. I don't know how 50 is supposed to feel, and I'm pretty sure I don't feel it anyway, but I wonder how long I'll be able to ignore my age. No use asking Dwayne; he's a lifelong distance runner and still looks and acts like my default image of him, the athletic collegian.

What really makes me feel young is that I keep changing, I keep learning, and I keep reinventing myself. In that respect I really look forward to becoming a full professor and being liberated to look around and see what opportunities are out there for me. It's the kind of new stage in life that gets me energized. Sometimes the years you put into a career are better than a time machine that could take you back to the beginning.

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

NWA

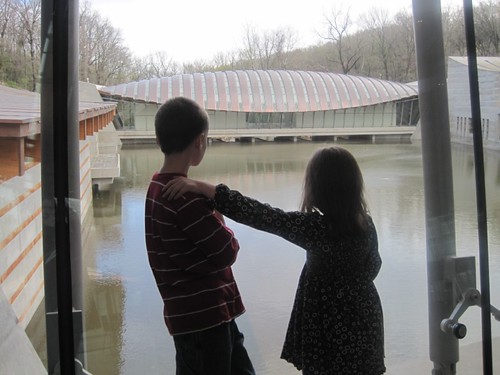

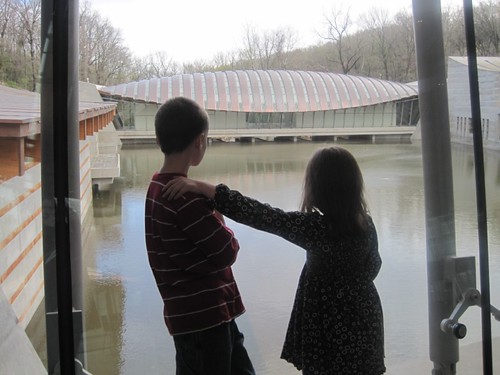

In this state, that stands for Northwest Arkansas. We planned a brief two-night trip up there during spring break week to see the new, highly acclaimed Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and to let the kids have the fun of a hotel stay. Then flooding rain was forecast for the first part of the week, with several inches possible at our destination, making us wonder if it was going to happen. We ended up having to drive in some uniformly soggy, foggy, ugly weather on the day we traveled, but the kids had an amazing time and we were introduced to a beautiful destination in the state -- so it was all worth it.

We like to stay at the Embassy Suites when we can because (a) suite, hooray, kids have their own room, and (b) the breakfast is a destination in itself. Archer calls it the Em Bass Ee Suites, emphasis on the "bass" like the fish.

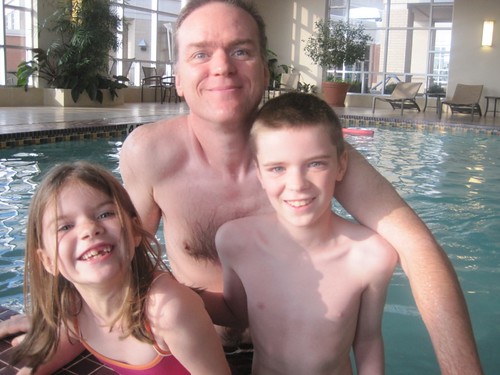

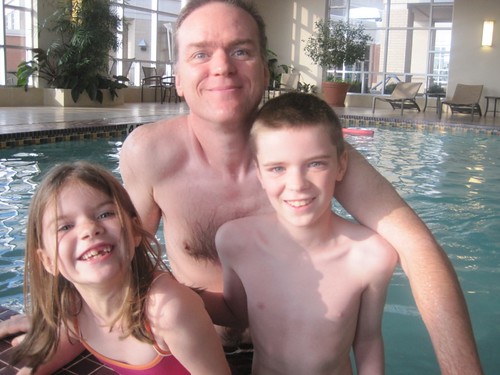

Our first swim of the warm season! The kids got right back in the swing of the water, and take a look at my newly svelte husband!

The museum doesn't open until 11 am (which I personally think is a huge missed opportunity -- we got there right when the doors opened and there was such a huge crowd that the upper parking lot was already full), so we visited the Wal-Mart Visitor Center on Bentonville's charming town square beforehand. Here the kids are posing by a coin-operated ride-on toy modeled on Sam Walton's famously unpretentious Ford pickup truck (the original is inside the Visitor Center exhibition space).

Waiting for lunch at the museum's beautiful Eleven cafe. When Archer trails his finger over something like this, these days it's because he is tracing the path of a pretend marble using the real world as a Marble Blast Gold level. "I just like to put a marble on that," he explains.

The museum was glorious. I can't wait to go back and explore it at my leisure. Here Cady Gray is recording her impressions of Adolph Gottlieb's "Trinity" in her museum guidebook.

Glow Bowl and Lazer Tag at Fast Lane, a giant arcade complex, rounded out the day perfectly.

And after all the weather drama, the drive home was a spectacular riot of spring sunshine, wildflowers, and burgeoning green. We'll definitely go back soon!

We like to stay at the Embassy Suites when we can because (a) suite, hooray, kids have their own room, and (b) the breakfast is a destination in itself. Archer calls it the Em Bass Ee Suites, emphasis on the "bass" like the fish.

Our first swim of the warm season! The kids got right back in the swing of the water, and take a look at my newly svelte husband!

The museum doesn't open until 11 am (which I personally think is a huge missed opportunity -- we got there right when the doors opened and there was such a huge crowd that the upper parking lot was already full), so we visited the Wal-Mart Visitor Center on Bentonville's charming town square beforehand. Here the kids are posing by a coin-operated ride-on toy modeled on Sam Walton's famously unpretentious Ford pickup truck (the original is inside the Visitor Center exhibition space).

Waiting for lunch at the museum's beautiful Eleven cafe. When Archer trails his finger over something like this, these days it's because he is tracing the path of a pretend marble using the real world as a Marble Blast Gold level. "I just like to put a marble on that," he explains.

The museum was glorious. I can't wait to go back and explore it at my leisure. Here Cady Gray is recording her impressions of Adolph Gottlieb's "Trinity" in her museum guidebook.

Glow Bowl and Lazer Tag at Fast Lane, a giant arcade complex, rounded out the day perfectly.

And after all the weather drama, the drive home was a spectacular riot of spring sunshine, wildflowers, and burgeoning green. We'll definitely go back soon!

Monday, March 19, 2012

With a smile on your face, and then do it again

Today's post about a sweater to celebrate change is at Toxophily.

It's a winter sweater for a year that winter never came, already put away to wait for the cold. No matter. Summer isn't forever.

It's a winter sweater for a year that winter never came, already put away to wait for the cold. No matter. Summer isn't forever.

Friday, March 16, 2012

Sweltering

Most of the country has been in a heat wave during the first half of March. Our temperatures have been in the mid eighties with relatively high humidity for this time of year.

That wouldn't be a big problem for me ordinarily. But the air conditioning in our building went out two weeks ago. A $25,000 motor for the chiller failed, and we got word late last week that it wouldn't be fixed before spring break.

So we've spent this week searching for ways to get a cross breeze going in our third and fourth floor classrooms and offices. Midweek the physical plant employees, apparently taking pity on us, delivered a truckload of box fans. That works well for rooms that can have more than one window open, or a door opposite the outside wall, but my office only has one window that opens in the far corner, and the air never gets to my desk on the other side of the room, much less the door leading into the student worker's tiny room and out into the rest of the office. If I get up and just stand between my door and the main office door, it seems 10 degrees cooler than when I'm at my desk.

Rather than try to hold class in our penthouse suite -- really an attic, with gable windows that don't open -- on the fourth floor where the building is likely to be most stifling, I've relocated for the week to a large room with ceiling fans and lots of windows. Even so, today I couldn't stand to be in there for the whole fifty minutes, and let the students out early.

It's way to early in the year to be too hot to work, but without any relief, it's difficult for any of us to concentrate and stay awake. Luckily for the students, spring break has begun, and they can broil on their beaches or sip icy drinks in well-chilled watering holes, as they prefer. I have to go back to the office on Monday, but maybe with fewer people and less on the schedule, the heat won't be quite as oppressive.

That wouldn't be a big problem for me ordinarily. But the air conditioning in our building went out two weeks ago. A $25,000 motor for the chiller failed, and we got word late last week that it wouldn't be fixed before spring break.

So we've spent this week searching for ways to get a cross breeze going in our third and fourth floor classrooms and offices. Midweek the physical plant employees, apparently taking pity on us, delivered a truckload of box fans. That works well for rooms that can have more than one window open, or a door opposite the outside wall, but my office only has one window that opens in the far corner, and the air never gets to my desk on the other side of the room, much less the door leading into the student worker's tiny room and out into the rest of the office. If I get up and just stand between my door and the main office door, it seems 10 degrees cooler than when I'm at my desk.

Rather than try to hold class in our penthouse suite -- really an attic, with gable windows that don't open -- on the fourth floor where the building is likely to be most stifling, I've relocated for the week to a large room with ceiling fans and lots of windows. Even so, today I couldn't stand to be in there for the whole fifty minutes, and let the students out early.

It's way to early in the year to be too hot to work, but without any relief, it's difficult for any of us to concentrate and stay awake. Luckily for the students, spring break has begun, and they can broil on their beaches or sip icy drinks in well-chilled watering holes, as they prefer. I have to go back to the office on Monday, but maybe with fewer people and less on the schedule, the heat won't be quite as oppressive.

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

Paper and string

Cady Gray is in an origami phase these days. I keep her regularly supplied with paper (ordered from Amazon in various patterns), and she fills our house with animals, objects, and geometric figures. She was introduced to string figures by a beloved babysitter, and practices the movements carefully.

I remember spending hours in the same pursuits when I was her age. I checked out every book in the various libraries to which I have access, creased them open, and crouched over them on my floor trying to interpret the various arrows and dotted lines in the line drawings.

It wasn't long before I (a) ran out of origami and string figure books, and (b) ran into frustration with directions I couldn't squint into clarity. And that was that. There was no place for me to go to make progress. And eventually, all those skills faded. I can't even remember how to make a teacup with a loop of string anymore.

Cady Gray is in a much more favorable position to keep learning and keep developing those habits in her hands. The reason is the internet. Origami sites -- not to mention paper planes, string figures, whatever you want to make out of those simple materials -- are plentiful. Best of all, you can follow along with illustrative photographs or videos (even better!) not limited in number or size by a paper publication.

I love to watch her create. And just by trying so many things, and practicing the basic skills over and over, she's able to develop a sense of the craft that helps her understand and attempt more advanced maneuvers. Who knows whether she'll outgrown paper and string like I did, or at about the same time? The important thing is that while her interest remains high, she has so many more options, so much better instruction, and is able to accomplish so much more.

I remember spending hours in the same pursuits when I was her age. I checked out every book in the various libraries to which I have access, creased them open, and crouched over them on my floor trying to interpret the various arrows and dotted lines in the line drawings.

It wasn't long before I (a) ran out of origami and string figure books, and (b) ran into frustration with directions I couldn't squint into clarity. And that was that. There was no place for me to go to make progress. And eventually, all those skills faded. I can't even remember how to make a teacup with a loop of string anymore.

Cady Gray is in a much more favorable position to keep learning and keep developing those habits in her hands. The reason is the internet. Origami sites -- not to mention paper planes, string figures, whatever you want to make out of those simple materials -- are plentiful. Best of all, you can follow along with illustrative photographs or videos (even better!) not limited in number or size by a paper publication.

I love to watch her create. And just by trying so many things, and practicing the basic skills over and over, she's able to develop a sense of the craft that helps her understand and attempt more advanced maneuvers. Who knows whether she'll outgrown paper and string like I did, or at about the same time? The important thing is that while her interest remains high, she has so many more options, so much better instruction, and is able to accomplish so much more.

Monday, March 12, 2012

Passing the Grade 4 ACTAAP

Archer wrote a personal narrative in his fifth grade literacy class. He created an outline, did a rough draft, and then revised. For content, he needed an introduction paragraph, a beginning events paragraph, a middle events paragraph, an ending events paragraph, and a concluding paragraph; the narrative had to include character(s), setting, problem clearly stated, transition words, and solution clearly stated. The rubric for style scored him on an effective lead, specific nouns, hefty verbs, adjectives, adverbs, figurative language, descriptions appeal to the senses, dialogue, and an effective conclusion.

The following personal narrative earned full points. I think you can clearly see how Archer adapts his own obsessions, the things he's interested in (like video games -- "Spin Off" is a Wii Party game) and the filters of quantification through which he experiences them, into a more standard format of storytelling with many of the external trappings of emotion and narrative arc. It's also interesting that he's the only character, putting himself in conversation and conflict not with another person, but with a test booklet and himself.

Passing the Grade 4 ACTAAP

It was the day of the first section of the ACTAAP Benchmark Test, Grade 4. I felt like my most stressful day ever. "This will DEFINITELY be a challenging test," I thought sadly, gulping.

I was starting the Grade 4 Benchmark in Marguerite Vann Elementary on April 15, 2011, at 8:30 in the morning. First, I did a bunch of Math sections quickly, but then, there was the first writing prompt. It read, "Write about a toy that you had for a while." "What toy should I choose?" I thought, worried. After pondering that for a long time, I finally chose my mini-pinball table. I scored 19 out of 20 points.

Soon enough, I faced a 2nd writing prompt that read, "Imagine you went to a castle that appeared overnight." I already knew the idea. I told proudly to myself, "This is going to be the easiest prompt ever!" I used "Spin-Off" castle with Takumi, Tatsuaki, and Lucia as my other characters. I would do a Spin-Off Battle against them and see who could bank up the most medals. I scored only 18 out of 20 points.

Then the Benchmark ended. After 4 reading sections with topics easy to understand, there were no more Open-Responses to complete. I explained, "The rest of this test will be more like the Iowa test, which has no open-responses." To my surprise, I was finished as quick as a wink!

At the end of the Benchmark, I was all exclamatory! I was also proud of myself. Have you ever faced a difficult test?

Saturday, March 10, 2012

A weekend away

For almost all of the last twelve years -- I don't think I've missed one since I moved to Arkansas -- I've been coming to Dallas on this weekend. It's the annual meeting of the Southwest Commission on Religious Studies, an umbrella organization that organizes a conference for the members of the American Academy of Religion, the Society of Biblical Literature, the American Schools of Oriental Research, and the Association for the Scientific Study of Religion in Texas and surrounding states.

Soon after I started attending, some of the organizers asked me to take leadership roles. I started as a chair of one of the program sessions, then served on the executive committee for the AAR's local branch, then agreed to become the AAR coordinator for the region. The six years of that job are almost up; next year will be my last in that position.

When I come to this meeting, I have a lot of jobs to do. Make decisions as a director of the Commission. Liaise between the AAR portion of the meeting and the meeting planner. Drum up attendance for the plenary. Give most of the reports at the AAR region's annual business meeting. And almost always, give a paper, moderate a session, sit on a panel.

This same weekend, my dad is going to a meeting that he's been attending for years. He's a member of the Kairos team that goes into a prison and spends three days with a group of inmates. The meeting involves months of preparation, like mine. It's packed with activities and a tight schedule, like mine. My dad has several leadership roles to enact, like I do. And there's a connection, too, with the premise of the meeting being religious. Mine is about the study of religion in an academic setting, and his is about practicing one religion's mandate to visit those in prison.

I'm sure readers will have their own opinion about which one is more in sync with their values and more salutary for society. As for me, well, we do good work here at the Southwest Commission on Religious Studies, but it's certainly neither as risky nor as courageous as the work of Kairos. I dare say that while our meeting may reach more people to advance their understanding in ways that improve their teaching of thousands of students, those people reached are already committed to that path, and so the advance is not revolutionary for most or all.

I dare say that the 40 inmates this Kairos weekend will reach are much more in need, and the effect on those men of being listened to and loved is potentially enormous, life-changing. College professors are used to being listened to. We have high social status. We are respected. The opposite is true, in all cases, for men in prison.

You might want to read about my dad's experience this weekend in his blog: http://walkinganewpath.blogspot.com. I am always humbled by what he relates. He may be the most self-critical blogger I read among the hundreds of feeds I follow. While serving others and seeking truth, he's always questioning his own motives and actions -- sometimes to a fault. I need to have more of that in my life, though. My confidence and ambition frequently lead me to believe that I'm a much better, more worthy person than anyone has a right to think themselves.

My dad has always been my role model. These days we often start from different premises in terms of our political and religious stances. The measure of our sincerity and effort surely is that sometimes we end up in the same place.

Those who are with Dad on his Kairos weekend don't have the same doctrine or politics as he does, either. Kairos is interdenominational, and folks participate from the liberal mainline churches, the nondenominational fellowships, the evangelicals and fundamentalists. When they read the Bible, some are reading God's dictation while others are reading human efforts to bear witness. But all are convinced that following the example of Jesus and Paul to pay special attention to society's outcasts is a good idea, good enough to take lots of time and effort and risk to undertake.

I'm convinced of it, too, and convicted. Here I am doing the work given me to do, and I'll do it with all my might, and I know it will make a difference and be appreciated. But how thankful I am that those rockier fields have found their laborers, too, and that I have some insight into their efforts through my dad.

Soon after I started attending, some of the organizers asked me to take leadership roles. I started as a chair of one of the program sessions, then served on the executive committee for the AAR's local branch, then agreed to become the AAR coordinator for the region. The six years of that job are almost up; next year will be my last in that position.

When I come to this meeting, I have a lot of jobs to do. Make decisions as a director of the Commission. Liaise between the AAR portion of the meeting and the meeting planner. Drum up attendance for the plenary. Give most of the reports at the AAR region's annual business meeting. And almost always, give a paper, moderate a session, sit on a panel.

This same weekend, my dad is going to a meeting that he's been attending for years. He's a member of the Kairos team that goes into a prison and spends three days with a group of inmates. The meeting involves months of preparation, like mine. It's packed with activities and a tight schedule, like mine. My dad has several leadership roles to enact, like I do. And there's a connection, too, with the premise of the meeting being religious. Mine is about the study of religion in an academic setting, and his is about practicing one religion's mandate to visit those in prison.

I'm sure readers will have their own opinion about which one is more in sync with their values and more salutary for society. As for me, well, we do good work here at the Southwest Commission on Religious Studies, but it's certainly neither as risky nor as courageous as the work of Kairos. I dare say that while our meeting may reach more people to advance their understanding in ways that improve their teaching of thousands of students, those people reached are already committed to that path, and so the advance is not revolutionary for most or all.

I dare say that the 40 inmates this Kairos weekend will reach are much more in need, and the effect on those men of being listened to and loved is potentially enormous, life-changing. College professors are used to being listened to. We have high social status. We are respected. The opposite is true, in all cases, for men in prison.

You might want to read about my dad's experience this weekend in his blog: http://walkinganewpath.blogspot.com. I am always humbled by what he relates. He may be the most self-critical blogger I read among the hundreds of feeds I follow. While serving others and seeking truth, he's always questioning his own motives and actions -- sometimes to a fault. I need to have more of that in my life, though. My confidence and ambition frequently lead me to believe that I'm a much better, more worthy person than anyone has a right to think themselves.

My dad has always been my role model. These days we often start from different premises in terms of our political and religious stances. The measure of our sincerity and effort surely is that sometimes we end up in the same place.

Those who are with Dad on his Kairos weekend don't have the same doctrine or politics as he does, either. Kairos is interdenominational, and folks participate from the liberal mainline churches, the nondenominational fellowships, the evangelicals and fundamentalists. When they read the Bible, some are reading God's dictation while others are reading human efforts to bear witness. But all are convinced that following the example of Jesus and Paul to pay special attention to society's outcasts is a good idea, good enough to take lots of time and effort and risk to undertake.

I'm convinced of it, too, and convicted. Here I am doing the work given me to do, and I'll do it with all my might, and I know it will make a difference and be appreciated. But how thankful I am that those rockier fields have found their laborers, too, and that I have some insight into their efforts through my dad.

Labels:

academia,

christianity's,

family,

personal history,

politics,

religion

Thursday, March 8, 2012

Knitting is a political act

In honor of International Women's Day, I'd like to consider not only how women have risen above their culturally designated "station" to change the world -- and those are often the women we recognize and celebrate, like Susan B. Anthony, Margaret Sanger, Madeline Albright, and Eleanor Roosevelt -- but also those who have changed the world by doing what society has assigned them to do.

The sneaky secret of empowerment is that it doesn't have to consist in grasping after a power beyond our mandated reach. It doesn't have to smash any ceilings. Not to belittle those who do; they are heroines, courageous beyond most of our imaginings. The backlash they suffer for daring to be more than what their peers imagine them to be is not something most of us would sign up for, or endure if we did.

But delving into the history of women's work, of the domestic sphere, as limiting and degrading as women can experience it to be (when it is all they are allowed to be), one finds powers that the defenders of the status quo have consistently overlooked.

The making of things empowers all of us. But it empowers women especially because the things we have been assigned historically to make are so fundamental, and therefore so radical. The cloth that we wove, the food that we cooked, the family structures we defined -- these are the root experiences of the human being. They are what we point to when we seek to differentiate our culture-bearing ancestors from their animal relatives.

As culture became more complex, women could chafe at being left on the ground floor, as it were. But oh, what a central position, what a powerful position that hearth and home can be. I'm not talking just about being a force behind the throne, influencing the men who go out into the world unwittingly carrying our ideas. I'm talking about shaping the physical world -- bending it around a needle, transforming it over a fire, shepherding it from helpless infant to independent adult.

When we knit, when we weave, we claim not only the powers that our politically active sisters gave to us over the past century. God bless them and what they did; no one in touch with their own humanity could wish it otherwise. But we can claim and exercise something deeper and more basic: the connection between our power to bear children and our power to beautify, adorn, warm, protect, and craft meaning into the world. Those powers meet at the hearthfire, where women inherited the jobs that were compatible with childrearing by virtue of being interruptible, not too dangerous, and practiced close to home. We found our pride and purpose there, something no one gave us and no one can take away. No matter how far we travel from that fundamental place, from those roots, we will always be able to call it back with the simple act of taking up the needle or the shuttle.

I'm following the Twitter feed of @RosiesWWII, the diary of a Seattle housewife who goes to work at Boeing after her husband joins the Army. Rosie's friend Betty is constantly knitting for the troops, including during the bus rides to and from the factory, and during her lunch break. Rosie tries to learn, too, but finds it confusing. So much for the notion that all women are born with those domestic skills in our genes. Like riveting, it's a learned skill. Like military training, it is passed from knowledgeable people to novices. Like all human occupations, it's a particular form of the urge to create merged with the imperative to survive.

Try telling Betty or Rosie that knitting is not a political act. That it's a hobby, a pastime, an unimportant and accidental aspect of life. Do it or don't do it -- you are making a political statement, about the way you want to be a woman. Be proud, be ashamed, be aggressive, be passive, keep it in a closet, take it out in the board room or the halls of government. They are all political acts. Because how we choose to be women, what we embrace and reject and leave behind and pick up again, our pasts and our futures, are political realities. They are our 95 theses, posted on the doors of our houses and offices and churches and trailing behind us as we move through our communities.

Whatever choice you make, do it consciously. I am not entirely comfortable with the new domesticity. I judge the way some women promote it or live it out. I am suspicious of their motives or their stance. Yet I recognize more and more every day that this is limiting and counterproductive. I realize this partly because of the judgment on whose receiving end I have been. When I continue on my path of making and connecting with the history of women in these crafts, I do so with the newly sober knowledge that the path has meanings I didn't choose.

Yet the only way to change those meanings is to keep choosing to enact the ones you believe in. Does my knitting limit me? No. Not being a knitter, being helpless before the tools and materials of the craft, laughing off my inabilities as if they were charming ineptitudes, afraid to begin lest I fail not only myself but my gender ... that was what limited me. And all those realities were my choice. They were not imposed on me by history or culture.

We are freer to acquire skills in this internet age than we ever have been before. Ignorance is no longer an excuse; the lack of a teacher in close proximity makes no difference. What inspires me and empowers me is that my connections are not only person to person as our bodies occupy the same time and space. We can be given power, inspiration, courage by people we will never meet in the flesh, thousands and millions of them, living out a way to be woman or man that we find freeing and creative -- and we can turn it into material reality. That's the key. Not just psychological liberation, but transforming matter, shaping the physical environment. Making it real.

How does participation in craft, especially those traditionally associated with women, give you power? I'd love to hear from you in the comments.

Thanks for reading the manifesto.

The sneaky secret of empowerment is that it doesn't have to consist in grasping after a power beyond our mandated reach. It doesn't have to smash any ceilings. Not to belittle those who do; they are heroines, courageous beyond most of our imaginings. The backlash they suffer for daring to be more than what their peers imagine them to be is not something most of us would sign up for, or endure if we did.

But delving into the history of women's work, of the domestic sphere, as limiting and degrading as women can experience it to be (when it is all they are allowed to be), one finds powers that the defenders of the status quo have consistently overlooked.

The making of things empowers all of us. But it empowers women especially because the things we have been assigned historically to make are so fundamental, and therefore so radical. The cloth that we wove, the food that we cooked, the family structures we defined -- these are the root experiences of the human being. They are what we point to when we seek to differentiate our culture-bearing ancestors from their animal relatives.

As culture became more complex, women could chafe at being left on the ground floor, as it were. But oh, what a central position, what a powerful position that hearth and home can be. I'm not talking just about being a force behind the throne, influencing the men who go out into the world unwittingly carrying our ideas. I'm talking about shaping the physical world -- bending it around a needle, transforming it over a fire, shepherding it from helpless infant to independent adult.

When we knit, when we weave, we claim not only the powers that our politically active sisters gave to us over the past century. God bless them and what they did; no one in touch with their own humanity could wish it otherwise. But we can claim and exercise something deeper and more basic: the connection between our power to bear children and our power to beautify, adorn, warm, protect, and craft meaning into the world. Those powers meet at the hearthfire, where women inherited the jobs that were compatible with childrearing by virtue of being interruptible, not too dangerous, and practiced close to home. We found our pride and purpose there, something no one gave us and no one can take away. No matter how far we travel from that fundamental place, from those roots, we will always be able to call it back with the simple act of taking up the needle or the shuttle.

I'm following the Twitter feed of @RosiesWWII, the diary of a Seattle housewife who goes to work at Boeing after her husband joins the Army. Rosie's friend Betty is constantly knitting for the troops, including during the bus rides to and from the factory, and during her lunch break. Rosie tries to learn, too, but finds it confusing. So much for the notion that all women are born with those domestic skills in our genes. Like riveting, it's a learned skill. Like military training, it is passed from knowledgeable people to novices. Like all human occupations, it's a particular form of the urge to create merged with the imperative to survive.

Try telling Betty or Rosie that knitting is not a political act. That it's a hobby, a pastime, an unimportant and accidental aspect of life. Do it or don't do it -- you are making a political statement, about the way you want to be a woman. Be proud, be ashamed, be aggressive, be passive, keep it in a closet, take it out in the board room or the halls of government. They are all political acts. Because how we choose to be women, what we embrace and reject and leave behind and pick up again, our pasts and our futures, are political realities. They are our 95 theses, posted on the doors of our houses and offices and churches and trailing behind us as we move through our communities.

Whatever choice you make, do it consciously. I am not entirely comfortable with the new domesticity. I judge the way some women promote it or live it out. I am suspicious of their motives or their stance. Yet I recognize more and more every day that this is limiting and counterproductive. I realize this partly because of the judgment on whose receiving end I have been. When I continue on my path of making and connecting with the history of women in these crafts, I do so with the newly sober knowledge that the path has meanings I didn't choose.

Yet the only way to change those meanings is to keep choosing to enact the ones you believe in. Does my knitting limit me? No. Not being a knitter, being helpless before the tools and materials of the craft, laughing off my inabilities as if they were charming ineptitudes, afraid to begin lest I fail not only myself but my gender ... that was what limited me. And all those realities were my choice. They were not imposed on me by history or culture.

We are freer to acquire skills in this internet age than we ever have been before. Ignorance is no longer an excuse; the lack of a teacher in close proximity makes no difference. What inspires me and empowers me is that my connections are not only person to person as our bodies occupy the same time and space. We can be given power, inspiration, courage by people we will never meet in the flesh, thousands and millions of them, living out a way to be woman or man that we find freeing and creative -- and we can turn it into material reality. That's the key. Not just psychological liberation, but transforming matter, shaping the physical environment. Making it real.

How does participation in craft, especially those traditionally associated with women, give you power? I'd love to hear from you in the comments.

Thanks for reading the manifesto.

Monday, March 5, 2012

Sticking to your knitting

Becoming a knitter six years ago has focused my attention on craft in a way that I've never experienced before. The relationship and frequent disconnect between technique and creativity is thrown into sharp relief by learning a new skill, and working to become better at it. I am intimately obsessed with the details of executing a craft discipline. I am often mystified by the ability of its master practitioners to internalize those details so thoroughly that they can imagine a world rendered through that set of motions, or see the world to be filled with the raw material that this craft transforms.

This afternoon I watched the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, about a sushi chef of 70 years experience who runs a ten-seat restaurant tucked into a hallway corner in the Tokyo subway underground. His creativity and perfectionism is so famous that people wait months or years for a reservation, and the minimum bill is 30,000 yen or about $350. The unprepossessing stall has three Michelin stars.

Much of the documentary focuses on the repetitive discipline of getting that good at something. Years of practice are required -- apprenticeships lasting most of a lifetime. Jiro, his sons and apprentices, and his adoring customers state over and over again that the key is to do only one thing. To do it every day, to aspire to reach ever new levels of achievement in that one solitary thing.

Years ago I might have found this intriguing but unrealistic. Most of our jobs require that we acquire many skills, and master few or none. But now, after thinking through the nature of craft with two seminar classes, I think there are ways for most people to take this as a challenge. How many of us develop an ability to perform in some area, and then expect that we will use this skill in a cruise control or autopilot mode while we advance ourselves in other ways? I wonder if teaching is like this for many academics. We learn to teach, we get reasonably good at it, and then we take that knife ou of the drawer and wield it whenever the occasion arises, without feeling we need to continue deepening our appreciation or understanding of that activity. We can do it, so we do it, and if we are still learning skills they are likely to be in areas related by professional affiliation but not necessarily by methodology or material, like administration, writing, research. It's a well-known fact that most academics consider the appropriate wage for teaching to be fewer and fewer assignments to teach as the years go on. Is such a system --- are such ambitions -- likely to produce great educators?

No one would expect a knitter to become a master of his craft, to reach the highest levels of skill, by doing something other than knitting. No one would expect an athlete to become a champion by doing something other than practicing her sport. Performing one's craft and reflecting on one's craft are the only two activities associated with honing one's craft. In how many areas of our culture do we expect, for some odd reason, perfection to be achieved by diffusion of effort rather than concentration?

This afternoon I watched the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, about a sushi chef of 70 years experience who runs a ten-seat restaurant tucked into a hallway corner in the Tokyo subway underground. His creativity and perfectionism is so famous that people wait months or years for a reservation, and the minimum bill is 30,000 yen or about $350. The unprepossessing stall has three Michelin stars.

Much of the documentary focuses on the repetitive discipline of getting that good at something. Years of practice are required -- apprenticeships lasting most of a lifetime. Jiro, his sons and apprentices, and his adoring customers state over and over again that the key is to do only one thing. To do it every day, to aspire to reach ever new levels of achievement in that one solitary thing.

Years ago I might have found this intriguing but unrealistic. Most of our jobs require that we acquire many skills, and master few or none. But now, after thinking through the nature of craft with two seminar classes, I think there are ways for most people to take this as a challenge. How many of us develop an ability to perform in some area, and then expect that we will use this skill in a cruise control or autopilot mode while we advance ourselves in other ways? I wonder if teaching is like this for many academics. We learn to teach, we get reasonably good at it, and then we take that knife ou of the drawer and wield it whenever the occasion arises, without feeling we need to continue deepening our appreciation or understanding of that activity. We can do it, so we do it, and if we are still learning skills they are likely to be in areas related by professional affiliation but not necessarily by methodology or material, like administration, writing, research. It's a well-known fact that most academics consider the appropriate wage for teaching to be fewer and fewer assignments to teach as the years go on. Is such a system --- are such ambitions -- likely to produce great educators?

No one would expect a knitter to become a master of his craft, to reach the highest levels of skill, by doing something other than knitting. No one would expect an athlete to become a champion by doing something other than practicing her sport. Performing one's craft and reflecting on one's craft are the only two activities associated with honing one's craft. In how many areas of our culture do we expect, for some odd reason, perfection to be achieved by diffusion of effort rather than concentration?

Sunday, March 4, 2012

Asbestos hands

I was making toast for my kids this morning. (In the toaster oven. Oven toast is the only way to go.). As I was putting on their plates, I remembered, as I always do, my mother's oft repeated joke about having asbestos hands.

Asbestos hands are something all mothers have. "Careful, that's hot!" you say to them as they pull a cookie sheet out of the oven or carry a casserole to the table. It's okay--they've developed mom callouses from doing that exact thing over and over. They're too busy and too confident to go rummaging for a hot pad. They can stand a few seconds of pain. You with your ordinary notions of temperature and comfort might not be able to imagine it, but all moms understand.

Asbestos hands might seem like a superpower. But it's really just the willingness to suffer a bit to get things done. In that way it is similar to that well-known motherly rule: you get the nice-looking portion, and she'll take to one that fell apart getting it out of the pan, or the one that's smaller, or misshapen, or missing half its frosting. Your plate should look good, your dinner shouldn't be delayed. Mom can take a little inconvenience.

I haven't mastered that last page of the Mom playbook, I admit. It's a good thing Noel's usually the one serving the meals. But I have the ideal, the model, in my head, never to be dislodged throughout my life. That's thanks to my mom, of course. We're all taught our parental roles by our parents. As I lift toast off the pan and transfer it to the kids' plates, enduring the momentary burn, I feel the personal satisfaction of self-sacrifice. For so many of us, that's the principle of motherhood our moms passed down to us. Whenever it serves us well, makes our homes a more welcoming place to be, or just avoids getting another utensil dirty (a principle that I learned from my dad, who takes pride in conserving silverware), they deserve the credit.

Asbestos hands are something all mothers have. "Careful, that's hot!" you say to them as they pull a cookie sheet out of the oven or carry a casserole to the table. It's okay--they've developed mom callouses from doing that exact thing over and over. They're too busy and too confident to go rummaging for a hot pad. They can stand a few seconds of pain. You with your ordinary notions of temperature and comfort might not be able to imagine it, but all moms understand.

Asbestos hands might seem like a superpower. But it's really just the willingness to suffer a bit to get things done. In that way it is similar to that well-known motherly rule: you get the nice-looking portion, and she'll take to one that fell apart getting it out of the pan, or the one that's smaller, or misshapen, or missing half its frosting. Your plate should look good, your dinner shouldn't be delayed. Mom can take a little inconvenience.

I haven't mastered that last page of the Mom playbook, I admit. It's a good thing Noel's usually the one serving the meals. But I have the ideal, the model, in my head, never to be dislodged throughout my life. That's thanks to my mom, of course. We're all taught our parental roles by our parents. As I lift toast off the pan and transfer it to the kids' plates, enduring the momentary burn, I feel the personal satisfaction of self-sacrifice. For so many of us, that's the principle of motherhood our moms passed down to us. Whenever it serves us well, makes our homes a more welcoming place to be, or just avoids getting another utensil dirty (a principle that I learned from my dad, who takes pride in conserving silverware), they deserve the credit.

Saturday, March 3, 2012

Waiting for karma

Earlier this week two days of tornados ripped through states to the north and east of us. I'm finding it hard to enjoy our beautiful outdoors, with its intact trees and undemolished houses, as a result. March is the top month for tornados in Arkansas. We are used to the threat, if still anxious about it. Why were these storms out of place? Why did other towns and families have the suffering that usually comes our way?

I've been delinquent on several important responsibilities in the last month of so. People I should have contacted, requests I should have made, organization I should have gotten underway. When I finally stepped up to the plate, very belatedly, I was somewhat dismayed to find out that I was not punished. My correspondants cooperated. Those I asked for help said yes. Schedules meshed. Stuff got covered. I couldn't help feeling guilty. It shouldn't have been that easy for me. I deserved something quite different.

I'm just waiting for the universe to balance itself out. Because truth didn't come with consequences recently, then some unmerited crap will have to fall on my head down the line. Maybe some bad behavior that got thrown my way this past week is the start of it, but to make up for all I should expect, for my sins and the probabilities that govern my life, there's a long way to go. And besides, it's not being wronged that I anticipate -- it's just the cards running cold. Plans falling through, serendipity absent, requests turned down, stuff breaking, inconveniences mounting to the same height as the undeserved conveniences I've shamefacedly enjoyed.

If my only penalty is monetary, I'll breathe a sigh of relief. Until the bill comes due, however, I'm going to have a hard time relaxing.

I've been delinquent on several important responsibilities in the last month of so. People I should have contacted, requests I should have made, organization I should have gotten underway. When I finally stepped up to the plate, very belatedly, I was somewhat dismayed to find out that I was not punished. My correspondants cooperated. Those I asked for help said yes. Schedules meshed. Stuff got covered. I couldn't help feeling guilty. It shouldn't have been that easy for me. I deserved something quite different.

I'm just waiting for the universe to balance itself out. Because truth didn't come with consequences recently, then some unmerited crap will have to fall on my head down the line. Maybe some bad behavior that got thrown my way this past week is the start of it, but to make up for all I should expect, for my sins and the probabilities that govern my life, there's a long way to go. And besides, it's not being wronged that I anticipate -- it's just the cards running cold. Plans falling through, serendipity absent, requests turned down, stuff breaking, inconveniences mounting to the same height as the undeserved conveniences I've shamefacedly enjoyed.

If my only penalty is monetary, I'll breathe a sigh of relief. Until the bill comes due, however, I'm going to have a hard time relaxing.

Thursday, March 1, 2012

2,000,000

Back in November 2010, Ravelry -- the greatest social networking site ever created, and I'm not just saying that because it is built around knitting -- hit one million registered users. Yesterday, Leap Day 2012, the two million mark was reached.

I had so much fun watching the countdown and celebration that I decided to collect my favorite parts of it in a Storify story. Here it is!

I had so much fun watching the countdown and celebration that I decided to collect my favorite parts of it in a Storify story. Here it is!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)