The day final grades for the semester are turned in is an anxious day for students and instructors alike. While students wait to find out what they made in their classes, A's and B's or D's and F's (worst of all is the C, which makes the course ineligible to be retaken for a new grade), we on the giving end are checking and rechecking our figures to make sure every grade is defensible.

When I started teaching, I regarded grades as more of a character assessment. A students, B students, C students -- I thought the difference became clear as the semester went on. My feedback was mostly concerned with reassuring the A students that their status was secure and letting the B and C students know what they needed to do to change their fate.

Since I've become a convert to more transparent systems of points and percentages, I've noticed two distinct advantages. One is that you find out things your intuition couldn't tell you. Today while double-checking the work of my upper-division seminar students, I found to my surprise that a particular member of the class had failed to turn in several pieces of work. This student had attended regularly and been prompt with some of the major assignments, but minor day-to-day work was spotty. When I went looking, I found other lacunae hidden in the mass of work that rolled in every week. A student I thought was going to be a low but solid A turned out to barely hang on to a B once all the points were totted up.

The other advantage is that when students (or their parents, or your boss) raises a question about the grade that was given, you have all the data you need to back it up. I make it a practice to be generous with my assessments, not wanting to end up with a good student being bumped down a letter grade (we have no pluses or minuses in our system) for ticky-tack points lost. And students who have been consistently subpar will get the grade they deserve even if I'm giving them a few too many points for each assignment. When a student asks if there's anything I can do about their grade, I can honestly say I've already done it.

It's a heavy responsibility to sit where we do, especially for my students where thousands of scholarship dollars can rest on a hundredth of a grade point in their average. Thank goodness I learned that responsibility demands accountability, and accountability demands accounting.

Showing posts with label pedagogy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label pedagogy. Show all posts

Monday, December 20, 2010

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Lab and workshop

My semester-long experiment -- an Honors seminar on handcrafting -- ended today with a celebration. The students knit, crocheted, read, discussed, wrote every day, recorded podcasts, and brainstormed with each other. They participated in two major service learning projects; above are the red scarves they made for the Orphan Foundation of America. Most of all, they thought about their own experiences in relation to the ideas in our texts, and worked hard to express those connections clearly in their writing.

I made some mistakes in the way I set up the course, and in some of the decisions I made executing it. But viewing it as an experiment, I could hardly be happier with the way it went. The students amazed me on a weekly basis with what they gleaned from our readings, the relationships they discovered during discussion, and how deeply they were willing to interrogate their own experiences, assumptions, and emotional responses.

This course taught me about implementing service learning. It taught me about balancing individual and group learning objectives, and giving students a say in crafting objectives and choosing among processes to achieve them. It taught me once again how amazing my students are, and how the insights I think are to be found in our materials are just a drop in the ocean of ideas that the students can synthesize out of what they are given.

What did my students learn? I think they'd say that they learned just how much they're capable of. I think they got a new sense of how they can contribute to their communities. And I think they now see ways of connecting the work of their minds and the work of their hands, to joyful effect.

Friday, December 10, 2010

Made by hand

Our society is divided into those who make with their hands, and those who make with their minds.

So too is our education divided into the liberal arts and vocational training. We train the mind, or we train the body; and especially in the former instance, we sometimes find it hard to deal with the ways in which motions of the body are involved in the motions of the mind.

There is some acknowledgement that manual skills are worthwhile in the sciences. More open and consistent are the fine arts; think how integral the body and its training is to the production of musicians, sculptors, and actors.

But it takes only a moment's reflection on the athletic department, and on the debates it raises in the context of education, to see how thoroughly we tend to separate the mind and the body in our practice.

One of the most intriguing experiences of my upper division class on handcrafting, now drawing to a close, has been the attempt to reintegrate the work of the hand and the work of the mind. At every class, students' hands have been busy, knitting, crocheting, winding yarn. At every class, too, we have worked through ideas in vigorous, sometimes knotty discussions.

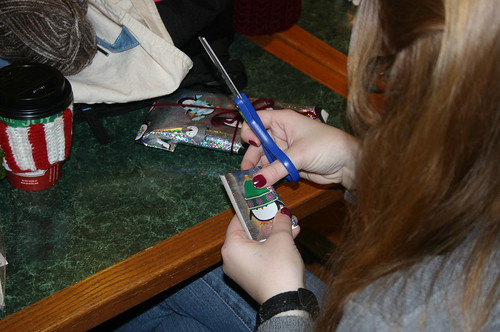

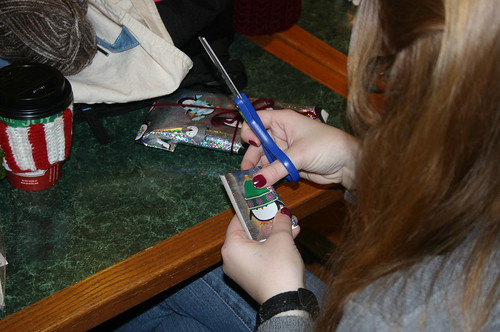

The last time we met, we engaged our hands in a new workshop activity -- wrapping our work for presentation to those for whom we made it. We bent our minds to the task of making sure everyone on our list was cared for.

While I cross-checked our roster of handmade hats with the list of recipients, students came forward in a steady stream to assume the tasks of cutting, labeling, fastening, and tying.

What connects the mind to the hands? The learning process itself, where we transform language and perceptions into understanding and finally replication. That day, as at every class meeting, someone showed someone else a new technique or a more efficient movement. The learner watched, formed an image of how to do it in his imagination, then tried it himself. So was the mind formed and the hands trained together.

And then we used our hands to reach out. To pass along their work.

To touch. To give. To hold. To lead.

As we stirred, we were stirred. As we created, we were created. Connecting minds and hands turned out to entail more than our own minds and our own hands. Some of the hands we touched, the ones that opened our packages and fitted our hats to their children's heads, will someday make something themselves -- re-enacting the images at the top of this post. What could be a better argument for an education that bridges the divide between mental and manual work?

So too is our education divided into the liberal arts and vocational training. We train the mind, or we train the body; and especially in the former instance, we sometimes find it hard to deal with the ways in which motions of the body are involved in the motions of the mind.

There is some acknowledgement that manual skills are worthwhile in the sciences. More open and consistent are the fine arts; think how integral the body and its training is to the production of musicians, sculptors, and actors.

But it takes only a moment's reflection on the athletic department, and on the debates it raises in the context of education, to see how thoroughly we tend to separate the mind and the body in our practice.

One of the most intriguing experiences of my upper division class on handcrafting, now drawing to a close, has been the attempt to reintegrate the work of the hand and the work of the mind. At every class, students' hands have been busy, knitting, crocheting, winding yarn. At every class, too, we have worked through ideas in vigorous, sometimes knotty discussions.

The last time we met, we engaged our hands in a new workshop activity -- wrapping our work for presentation to those for whom we made it. We bent our minds to the task of making sure everyone on our list was cared for.

While I cross-checked our roster of handmade hats with the list of recipients, students came forward in a steady stream to assume the tasks of cutting, labeling, fastening, and tying.

What connects the mind to the hands? The learning process itself, where we transform language and perceptions into understanding and finally replication. That day, as at every class meeting, someone showed someone else a new technique or a more efficient movement. The learner watched, formed an image of how to do it in his imagination, then tried it himself. So was the mind formed and the hands trained together.

And then we used our hands to reach out. To pass along their work.

To touch. To give. To hold. To lead.

As we stirred, we were stirred. As we created, we were created. Connecting minds and hands turned out to entail more than our own minds and our own hands. Some of the hands we touched, the ones that opened our packages and fitted our hats to their children's heads, will someday make something themselves -- re-enacting the images at the top of this post. What could be a better argument for an education that bridges the divide between mental and manual work?

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Self promotion

Gradually, as my teaching style has changed from traditional and classroom-focused to experimental and real-world-project-focused, I've had to adopt another style that didn't come naturally. I've had to be an advocate for the accomplishments of my students out in that real world.

Doing something that makes a public difference is all well and good in itself. But how much it's magnified when other people know you've done it! Most of these projects aim to accomplish something concrete, but almost all of them can handle an additional goal -- to let other people know about the need that the project is addressing. To achieve that goal, you need to utilize the communication channels that exist to get the word out. And that means not being shy about asking people to open those doors for you.

Some are under your control. Make a website; put up a YouTube video; link to them from your Facebook or Twitter feed. But beyond that, you need others' help. Ask your friends to retweet and spread the word. Call the newspaper. Get a photographer to your event. Suggest a story to the campus newsletter. Invite participation by folks beyond your classroom walls.

If any of that comes through, it means what you're doing has intrinsic interest. Others can participate in the awareness campaign for reasons that mesh with their own goals. Then the ball's back in your court -- publicize their publicity through the networks of which you're a part.

The reasons for doing so aren't self-aggrandizement. It's a further step in making the activity real and consequential. The more the outside world takes an interest -- and takes up the cause -- the more the students at the center of it all aren't just doing a class project. They're setting something in motion that is bigger than their grade, bigger than the semester, bigger than the academic game we all learn to play. They can start something that attracts other people -- that has gravity, that has legs, that inspires and moves people to action.

That's reason enough to let go of any remaining humility and recruit anyone you can to help you shout it from the rooftops.

Doing something that makes a public difference is all well and good in itself. But how much it's magnified when other people know you've done it! Most of these projects aim to accomplish something concrete, but almost all of them can handle an additional goal -- to let other people know about the need that the project is addressing. To achieve that goal, you need to utilize the communication channels that exist to get the word out. And that means not being shy about asking people to open those doors for you.

Some are under your control. Make a website; put up a YouTube video; link to them from your Facebook or Twitter feed. But beyond that, you need others' help. Ask your friends to retweet and spread the word. Call the newspaper. Get a photographer to your event. Suggest a story to the campus newsletter. Invite participation by folks beyond your classroom walls.

If any of that comes through, it means what you're doing has intrinsic interest. Others can participate in the awareness campaign for reasons that mesh with their own goals. Then the ball's back in your court -- publicize their publicity through the networks of which you're a part.

The reasons for doing so aren't self-aggrandizement. It's a further step in making the activity real and consequential. The more the outside world takes an interest -- and takes up the cause -- the more the students at the center of it all aren't just doing a class project. They're setting something in motion that is bigger than their grade, bigger than the semester, bigger than the academic game we all learn to play. They can start something that attracts other people -- that has gravity, that has legs, that inspires and moves people to action.

That's reason enough to let go of any remaining humility and recruit anyone you can to help you shout it from the rooftops.

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Instructables

In my teaching, I've come to despise answering a certain type of question. Not the type that seeks understanding or knowledge or a clarifying idea or a helpful framework. The kind that inquires about the logistics of a class activity or assignment.

I don't like answering those kind of questions because (a) it's inefficient, and (b) it's a back-end scramble to cover a front-end failure. When students ask about logistics, the answer -- delivered orally -- is inevitably less structured and comprehensive than good instructions should be. It's also heard differentially by the class; even if the person who asked the question gets what he wants, others might not be engaged, not needing the information right at that moment -- meaning they won't have it when they do need it. And of course, the answer's not integrated into the point-of-need instructions that are posted where students can access them when they're actually working on the assignment. This leads to a lot of duplicate questions, which is not only wasted time but the potential for telling the various questioners slightly different things.

Instead, I tend to write extraordinarily detailed assignments. And I've been gravitating toward a question-and-answer format that reduces the need for students to have to intuit my structural logic. Students what to know what they're being asked to do, how they're supposed to do it, where to find the tools they'll need, how they'll be evaluated, in what form to turn it in, when it's due. So I'm writing assignments with sections headed by those very questions. I wrote a blog assignment and a podcasting assignment this morning in about two and a half intense hours of work. Here are some of the headings:

I don't like answering those kind of questions because (a) it's inefficient, and (b) it's a back-end scramble to cover a front-end failure. When students ask about logistics, the answer -- delivered orally -- is inevitably less structured and comprehensive than good instructions should be. It's also heard differentially by the class; even if the person who asked the question gets what he wants, others might not be engaged, not needing the information right at that moment -- meaning they won't have it when they do need it. And of course, the answer's not integrated into the point-of-need instructions that are posted where students can access them when they're actually working on the assignment. This leads to a lot of duplicate questions, which is not only wasted time but the potential for telling the various questioners slightly different things.

Instead, I tend to write extraordinarily detailed assignments. And I've been gravitating toward a question-and-answer format that reduces the need for students to have to intuit my structural logic. Students what to know what they're being asked to do, how they're supposed to do it, where to find the tools they'll need, how they'll be evaluated, in what form to turn it in, when it's due. So I'm writing assignments with sections headed by those very questions. I wrote a blog assignment and a podcasting assignment this morning in about two and a half intense hours of work. Here are some of the headings:

- Where's the blog?

- When do I write?

- Can I write when it's not my turn?

- What should I write about?

- Halp halp, I can't post/edit/upload a picture/etc!

- How do we make a podcast?

- How long should our podcast be?

- What should we talk about?

- We've recorded. What do we do now?

- When is our podcast due?

Communicating with students is an underappreciated art. Many instructors feel like the students should just be able to get it -- that it's their responsibility to extract the relevant information however the instructor chooses to present it. I sometimes think we could all use a good technical writing short course. If we put in enough effort and thought on the front end, delivering what students need know in a format where they can find and utilize it, then we save ourselves (and our students) a lot of frustration on the back end when we don't have to clarify our vagaries piecemeal, incompletely, and repeatedly.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Experience, the best teacher

I spent the day with a few dozen colleagues at a workshop on service learning, and we found ourselves having to confront some difficult questions about our teaching and about our students' learning. From the evidence of the discussion, there are three basic questions that arise when we contemplate including service learning or experiential learning in our classes for the first time.

First we ask: Can I do this? Do I, the instructor, have the wherewithal to do this new thing? Usually we do not doubt our innate capacity to innovate or lead; we may, however, doubt that needed resources will be forthcoming, or feel that we lack models to follow. In other words, we believe that we could do it if we had a guide, or if we had access to needed moneys or personnel. It's external support we lack, not internal ability.

Then we ask: What would we do? What organizations in my community could I plug into? What opportunities exist that I would like to guide the students towards? Again, few of us professors would argue that the organizations and opportunities don't exist or are inaccessible. We may not know all about them, but we know that just a little research (something we're quite good at) would turn them up. We may even, if we think about it, realize that those organizations have people in them who are knowledgeable about and capable of coordinating volunteers and projects -- the kinds of things we'd be approaching them about.

It's the third question where we shift our thinking, often without realizing it. Can my students do this? While it would never occur to most of us to doubt our ability to create such a class and lead our students through it, we're often quite ready to believe that our students are incapable of navigating the path we map out for them. We may question their readiness for independent work, for critical self-reflection, for project-based learning, for collaboration, for responsibility, for self-assessment, for power, for the chance to determine the success or failure of the class, for a say. In the end, I believe this is the reason most professors who decide not to pursue service learning give: My students couldn't handle that.

And yet, as our facilitator demonstrated most forcefully today, these pedagogical methods challenge almost everything tradition tells us about what teaching is and what learning is. If we set them aside because of assumptions -- or even because of our personal experience -- about what students are capable of based on those traditional frameworks, we are letting conventional wisdom dictate to us at the very point where we are convinced (in the other two questions) of the viability of this path.

I know that I teach an exceptional group of students. But even in that rarified circle, I hear distressingly definitive statements being made about what they cannot do. I can only say "amen" to the facilitator's words today: If we are sure they can't do it, then it's a sure thing that they won't.

Thursday, May 6, 2010

A happy ending

A semester-long college course -- especially a brand new one -- is a tightrope act. Is there a clear line from one end to the other? Are there any gaps where students might stumble? In some respect, you can't know the answers to those questions until you've gone all the way through it.

I just reached the end of a course that I've never taught before. It was a hybrid between a film aesthetics course I've done in various forms many times, and a crash course on digital filmmaking that I could never teach. Luckily I had a co-instructor who knew how to do that second part. But I mostly proposed the structuring, because I'm the experienced pedagogue. I strung the tightrope.

And two-thirds of the way across, I found that students were falling off right and left. I had given them what I thought was a generous cushion of time to work in groups to plan, shoot, and edit a short film. The students were divided into six groups. We have two high-end Canon cameras. I arranged things so two groups could have a camera for a week at a time, with two weeks left at the end where groups could check out cameras short-term for pickup shots. I shuffled the schedule a million ways to make it work.

But what I didn't know was that I wasn't including an important step. The footage they shot had to be digitized before they could edit it. The digitizing could only be done with the camera. So if another group took the camera for shooting, the previous group couldn't get their footage digitized. The time I had provided on the syllabus for them to edit got eaten up by waiting for the chance to make their footage usable. One group, the unluckiest of the bunch, got their camera late from the previous users and only had 24 hours to shoot before the next group needed it. They had to wait for the pickup shots slot to get the bulk of their footage. And the digitizing lag/bottleneck meant that they got their footage to edit less than 24 hours before the project was due.

Yet tonight's final exam film festival featured all six films, even the one from the snakebit group. That one was rough, certainly, but its energy and comedy elicited roars of laughter from the assembled students and guests. The groups invited the actors, extras, and friends that they recruited to work on their films to witness the final products. Every single one contained some memorable and sophisticated effect, and a couple were quite effective throughout. The audience laughed, gasped, and marveled for the whole ninety minutes. Despite all the unintentional debris I left for the students to hurdle on their way across the tightrope, they all made it to the other side.

I can't take any credit for their perseverance. I can only be glad that they didn't let my mistakes derail them. If there's a next time, I'll know better how to smooth the way for the students who follow -- thanks to the students this time who endured the roughest ride.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)