I always watched Wide World of Sports. It was a Sunday afternoon ritual. Jim McKay, Howard Cosell, those yellow blazers, and whatever random sporting event they were covering. (Based on this early experience, I would have projected cliff diving to feature much more prominently in my life than it actually has.)

I watched with my dad, mostly. Probably my brothers were around, too. But it was my dad I was aware of, in the room, following the standings of the giant slalom or weightlifting. And it's my dad I thought of immediately when I heard this morning that Muhammad Ali had died.

Wide World of Sports was the Muhammad Ali show for a lot of those years (with short breaks during which it become the Evel Knievel show). Howard Cosell was Ali's foil. Wide World previewed the fights, showed the fights, interviewed Ali before, after, and for all I can remember, during the fights. Cowell and Ali, Ali and Cosell, verbally jabbing at each other, engaged in a joyous dance, each endlessly amused by the other, needing each other.

Ali was on Wide World so much because he was a personality. He must have been great for ratings. And because of that, I felt ... odd about him. It wasn't always about the sports, is what I realized. Often it was just about putting entertaining, unpredictable people on air and waiting for the fireworks. I intuited, in a childish way, that Cosell was something of a parasite, when it came to Ali. I was disturbed that he could get so far by so blatantly hitching his wagon to a star. (There was more to Cosell, too, I know, but the relationship still felt one-sided.)

What I wasn't quite sure about was whether I should be equally disturbed by Ali playing along. Was he in on the joke? Was he doing an act for the cameras? Was he giving the people what they want? Or was he desperate for attention? In my world, one was expected to be self-deprecating and gracious. All the boasting and grandstanding -- it made me uncomfortable. And the Wide World machine enabling and encouraging it, egging him on. I really did not know what to think.

Boxing was different in those days, for sports fans. Now the title fights are all on pay-per-view. They're still very popular, no doubt, but they aren't a mass-market product. Back then they were on network television and we all watched them avidly. When Ali fought, that's when my confusion melted away. He was actually engaged in a different sport than his opponents. He was playing a different game. He could tell the whole world his exact strategy, like the "rope-a-dope" (which I remember so well), and still nobody could do anything about it.

Someone who could back up his braggadocio with actual domination -- someone who was bigger than life in a seventies wide-lapel suit and in boxing trunks -- someone who made for equally great copy in his interviews as in his contests. That's what I wasn't prepared to understand. Someone who always played his own game and expected us to come to him, in the media world and in the ring alike. I didn't know how to judge that, how to value it.

Race was a factor, there's no doubt. We were privileged white folks. I had very few black classmates in my private schools, and at least in the arenas where I interacted with them, they displayed few cultural traits or habits that weren't my own. We employed a black maid. Dad interacted with black truck drivers or other workers in his job sometimes, I knew. Our large and prosperous church was all white. Obviously I wasn't comfortable with black assertiveness, black speech patterns, black politics, black power. Obviously I was bound to see it as alien, as a threat, even if I had the most generous of curiosities.

I watched with my dad, and part of my discomfort was my suspicion that he wasn't okay with the changes in sports that Ali represented. I idolized and learned my sports fandom from my dad. I didn't know whether I should be okay with them or not. But we kept watching, together. There was never any question that when it came to the fights, these were monumental events, and that Ali's triumphs represented a historic dominance of the sport.

That ambivalence mixed with fascination defined my view of Ali during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Boxing moved away from the mass market, and I stopped paying attention to it. It wasn't until the 1996 Atlanta Olympics (which Noel and I attended) that Ali re-entered my consciousness in a big way. I was stunned by the significance of that event, by the courage of the fighter bowed by disease standing up once again to be seen, taking it as his due. In subsequent years, the documentaries When We Were Kings and The Trials of Muhammad Ali (both tremendous, powerful films) filled in the massive gaps in my knowledge. I don't remember Cosell asking about, or Ali talking about, resisting the draft -- maybe he did and I just didn't know what was going on. I was ignorant of all the context surrounding the Rumble in the Jungle. I was ignorant. I'm glad in a way that I was too conflicted to have a strong opinion, besides just fascination. I didn't know enough to have an opinion.

Since then I've read David Remnick's biography. I've read many great sportswriters painting a picture of the man, in all his dimensions. (Check out Jerry Izenberg's obit, just for a sample.) He has only grown larger, more imposing, more improbable with each detail. What I wasn't equipped to appreciate until only a few years ago, I think (having been fortunate enough to be educated by many eloquent, thoughtful, forceful, patient people of color on social media, especially), was how important he was as a black man. How his politics and religion unapologetically flowed from that singularly American experience. How paying attention to that could teach me things I could never learn on my own.

Muhammad Ali made me a better, more well-rounded, more nuanced and perceptive person for paying attention to him, for thinking through what he showed me, especially when it was uncomfortable for me to do so.

Yet he didn't exist for my benefit. That's what made him the greatest. He was exactly the person he wanted to be, almost from the moment he burst onto the scene until the day he died. I'd thank him, only it's beside the point. Better to say to the universe: We didn't deserve that. We're grateful.

Showing posts with label r.i.p.. Show all posts

Showing posts with label r.i.p.. Show all posts

Saturday, June 4, 2016

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

R.I.P. Richard Rutt

Last year, as I embarked on the beginnings of a multiyear and multistage project on theology and handwork, I read the only comprehensive history of knitting to be published in English in the last fifty years. The author of this indispensable work, A History of Hand Knitting, was Richard Rutt. It was clear from his extraordinarily winning book that he was an amateur historian, with very definite opinions and biases on controversial topics in the field, and also that he was a charming Englishman with a passion for his subject and plenty of energy for research.

On August 3, Rutt died in the UK at the age of 86. Reading through some of the obituaries and remembrances posted after his death, I find what an interesting and multifaceted man he was. As an Anglican priest, he rose to the rank of Bishop of Leicester after serving almost 20 years as a missionary in South Korea. In 1994 he switched allegiance to the Catholic church, was ordained as a priest therein (although he remained married), and was made an honorary prelate (with the title of monsignor) in 2009. The impetus for his conversion to Catholicism was not opposition to female priests or other liberalisms, as with more recent Anglican defections, but dissatisfaction with moves to bring other Protestant groups into full communion with the Church of England.

The bulk of his published works related to Chinese language translation and Korean studies, some of which were groundbreaking. Knitters valued him for his singular History, however, as well as for a few patterns published in English magazines. He was known for knitting his own vestments, bishop's miter, and sacramental textiles. At the time of his death he was the president of the Knitting and Crochet Guild, a national organization that publishes the journal SlipKnot.

Rutt's book was one of the first pieces of my serious research into craft history, and produced a wealth of notes that will form a strand in my work going forward. Rest in piece, Monsignor Rutt.

On August 3, Rutt died in the UK at the age of 86. Reading through some of the obituaries and remembrances posted after his death, I find what an interesting and multifaceted man he was. As an Anglican priest, he rose to the rank of Bishop of Leicester after serving almost 20 years as a missionary in South Korea. In 1994 he switched allegiance to the Catholic church, was ordained as a priest therein (although he remained married), and was made an honorary prelate (with the title of monsignor) in 2009. The impetus for his conversion to Catholicism was not opposition to female priests or other liberalisms, as with more recent Anglican defections, but dissatisfaction with moves to bring other Protestant groups into full communion with the Church of England.

The bulk of his published works related to Chinese language translation and Korean studies, some of which were groundbreaking. Knitters valued him for his singular History, however, as well as for a few patterns published in English magazines. He was known for knitting his own vestments, bishop's miter, and sacramental textiles. At the time of his death he was the president of the Knitting and Crochet Guild, a national organization that publishes the journal SlipKnot.

Rutt's book was one of the first pieces of my serious research into craft history, and produced a wealth of notes that will form a strand in my work going forward. Rest in piece, Monsignor Rutt.

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Long live the king

Although I grew up in the seventies, I had no direct relationship with Farrah Fawcett. I didn't watch Charlie's Angels, I didn't have that poster on my wall or have a t-shirt with her picture on it. In other words, I was not a boy. Farrah meant something to me, though -- she was married to my all-time biggest crush, Lee Majors. I can still see in my mind's eye a photograph of them together with their son in a Scholastic paperback bio of Majors I got from the Weekly Reader.

So even though it was surprising that one of the icons of the decade of my upbringing died yesterday, it wasn't shocking.

Michael Jackson dead? Now that's a shock to me. Because I did -- and do -- have a relationship with him.

When I was in ninth grade, my best friend Vicky and I choreographed an aerobics routine to "Don't Stop Till You Get Enough" for a PE assignment. I don't remember what the moves were, and I sure don't want to remember my chunky self performing them. But I will never forget the liberating feeling of dancing to that song -- and to all of Off The Wall, one of my favorite albums of all time.

When I was in eleventh grade, Thriller came out. Each January, the glee club at my school went on a tour. I don't know where we were that year, but I do remember a hotel ballroom, a big party, and Mrs. Greene, our director, dancing on a table to "Beat It." And once again, I can feel exactly what it was like to let go of all inhibitions while we grooved along, lost in the collective moment.

If you didn't live through that age of top 40 radio and the birth of MTV, you have no idea what it means for a pop culture event to be completely ubiquitous. There were no niches; everyone was in the same media melting pot. And Thriller saturated every medium that existed -- television, radio, and print.

And when I was older and more discerning about the music of my upbringing, I found myself able to embrace the music of Michael Jackson wholeheartedly, without any intellectual or aesthetic reservations. He was simply brilliant at what he did. As his bizarre personal life came to dominate the tabloid media, I feared that this would be his legacy -- the freak, the creep, the mutilated oddball. Would anyone be able to hear the music anymore and recognize the giant stature of those recorded (and videotaped) acommplishments?

Like everyone, I have a perverse fascination with the reclusive, semi-human existence Jackson's been living for the past two decades. We all want to understand how immense fame and fortune can turn someone from a man into ... something else, something with strange appetites and impenetrable motivations and twisted desires.

Yet there was nothing oblique about the music that he made or the pleasure that it has the power to bring. And it's not just the early hits, before he got weird. When I listen to the Michael Jackson playlist on my iPod, I get especially excited when "Black or White" comes up. Its album, Dangerous, was number one on the Billboard 200 as 1991 turned into 1992. The album it displaced at #1? Achtung, Baby. The album that followed it? Nevermind. Yet right in the center of this epoch-making moment in rock music is Michael Jackson, with a song that I find irresistible.

For some of us, I dare say, this is a version of Elvis' death. It's equally hard to believe because of the magnitude of Jackson's musical and cultural gravity. And I don't think it will be just crazed fanatics shedding a tear. No one should be ashamed to grieve for a man who made art that changed our lives.

So even though it was surprising that one of the icons of the decade of my upbringing died yesterday, it wasn't shocking.

Michael Jackson dead? Now that's a shock to me. Because I did -- and do -- have a relationship with him.

When I was in ninth grade, my best friend Vicky and I choreographed an aerobics routine to "Don't Stop Till You Get Enough" for a PE assignment. I don't remember what the moves were, and I sure don't want to remember my chunky self performing them. But I will never forget the liberating feeling of dancing to that song -- and to all of Off The Wall, one of my favorite albums of all time.

When I was in eleventh grade, Thriller came out. Each January, the glee club at my school went on a tour. I don't know where we were that year, but I do remember a hotel ballroom, a big party, and Mrs. Greene, our director, dancing on a table to "Beat It." And once again, I can feel exactly what it was like to let go of all inhibitions while we grooved along, lost in the collective moment.

If you didn't live through that age of top 40 radio and the birth of MTV, you have no idea what it means for a pop culture event to be completely ubiquitous. There were no niches; everyone was in the same media melting pot. And Thriller saturated every medium that existed -- television, radio, and print.

And when I was older and more discerning about the music of my upbringing, I found myself able to embrace the music of Michael Jackson wholeheartedly, without any intellectual or aesthetic reservations. He was simply brilliant at what he did. As his bizarre personal life came to dominate the tabloid media, I feared that this would be his legacy -- the freak, the creep, the mutilated oddball. Would anyone be able to hear the music anymore and recognize the giant stature of those recorded (and videotaped) acommplishments?

Like everyone, I have a perverse fascination with the reclusive, semi-human existence Jackson's been living for the past two decades. We all want to understand how immense fame and fortune can turn someone from a man into ... something else, something with strange appetites and impenetrable motivations and twisted desires.

Yet there was nothing oblique about the music that he made or the pleasure that it has the power to bring. And it's not just the early hits, before he got weird. When I listen to the Michael Jackson playlist on my iPod, I get especially excited when "Black or White" comes up. Its album, Dangerous, was number one on the Billboard 200 as 1991 turned into 1992. The album it displaced at #1? Achtung, Baby. The album that followed it? Nevermind. Yet right in the center of this epoch-making moment in rock music is Michael Jackson, with a song that I find irresistible.

For some of us, I dare say, this is a version of Elvis' death. It's equally hard to believe because of the magnitude of Jackson's musical and cultural gravity. And I don't think it will be just crazed fanatics shedding a tear. No one should be ashamed to grieve for a man who made art that changed our lives.

Monday, October 6, 2008

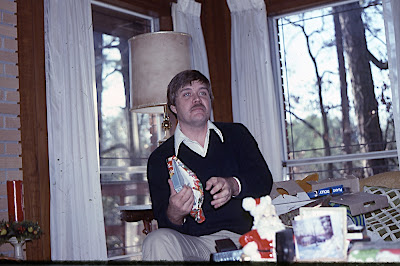

My uncle Dave

This is my uncle Dave. It's 1978, and he's at my grandparents' house on Lake Chickamauga opening Christmas presents.

I can hear him right now, as he rips open the paper. "Oh," he might say in his soft, expressive voice. "What's this? Oh my! Well, thankyouverymuch!" Uncle Dave was always understated. He had a low, ready laugh. He talked quickly, and usually quietly.

Every Christmas I looked forward to my present from Uncle Dave. He always got something unusual -- something a little exotic, usually with no practical purpose. I could never predict his presents. They were always a total surprise. I treasured them for their complete lack of utility.

Uncle Dave was my father's younger brother, the second of three boys. He studied music and became a renowned and accomplished pipe organist. He was the first in my father's family to get a Ph.D.

Uncle Dave was gay. Nobody in the family talked about it. I don't know anything about his relationships. I have vague memories of hearing my parents talk about his roommate. Of course I didn't understand anything about it until I was well into adulthood.

My uncle Dave died on Saturday, of complications brought on after a fall. I hadn't seen him in many, many years. I hope that for all those years of our separation he lived as I remember him: a world traveler, an effortless artist, a keeper of rare and unusual gifts.

Saturday, September 27, 2008

The law west of the Pecos

When I heard the news this morning that Paul Newman had died, I immediately thought of his roles in The Verdict and The Hudsucker Proxy. Those were movies that meant a lot to me when they came out, and that I still remember as daring experiments in style and mood.

Although The Verdict was hardly groundbreaking, it came out when I was a junior in high school and was just beginning to be able to attend movies. I was shaken by its bleakness and moved by Newman's vulnerability and gravitas. Sidney Lumet, as he nearly always did, made me feel like an adult, and I loved the movie -- and Newman -- for that. What a cadre of nominees for the Best Actor Oscar that year -- Ben Kingsley (the winner for Gandhi), Newman, Dustin Hoffman (Tootsie), Peter O'Toole (My Favorite Year). (I'll pass over Jack Lemmon (Missing) without comment.)

Newman isn't indispensible to The Hudsucker Proxy, really, but his role symbolizes the seriousness with which he took his craft and his never-waning interest in cinematic experimentation. For such a box-office stalwart, Newman never seemed to sa

y no to the chance to work with great filmmakers on risky scripts. He stayed on the cutting edge right to the end.

But the performance that I'll always treasure most is his cranky, quirky star turn as Judge Roy Bean in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, an oddball John Huston/John Milius comic western from 1972. It was one of a handful of pop culture artifacts that my circle in Athens was obsessed with. We quoted it incessantly.

Although The Verdict was hardly groundbreaking, it came out when I was a junior in high school and was just beginning to be able to attend movies. I was shaken by its bleakness and moved by Newman's vulnerability and gravitas. Sidney Lumet, as he nearly always did, made me feel like an adult, and I loved the movie -- and Newman -- for that. What a cadre of nominees for the Best Actor Oscar that year -- Ben Kingsley (the winner for Gandhi), Newman, Dustin Hoffman (Tootsie), Peter O'Toole (My Favorite Year). (I'll pass over Jack Lemmon (Missing) without comment.)

Newman isn't indispensible to The Hudsucker Proxy, really, but his role symbolizes the seriousness with which he took his craft and his never-waning interest in cinematic experimentation. For such a box-office stalwart, Newman never seemed to sa

y no to the chance to work with great filmmakers on risky scripts. He stayed on the cutting edge right to the end.

But the performance that I'll always treasure most is his cranky, quirky star turn as Judge Roy Bean in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, an oddball John Huston/John Milius comic western from 1972. It was one of a handful of pop culture artifacts that my circle in Athens was obsessed with. We quoted it incessantly.

- "Justice is the handmaiden of the law." "But you said the law is the handmaiden of justice!" "Works both ways."

- "This was the original Bad Bob. The albino."

- "I'm very advanced in my views and outspoken."

Monday, August 4, 2008

Skip Caray, 1939-2008

Skip Caray has been a part of my life ever since Braves baseball has been a part of my life. Baseball wasn't my favorite sport growing up -- that would be NCAA basketball and football -- but it wasn't long into my adulthood before I embraced America's greatest contribution to the world of sport.

We were always Braves fans in Chattanooga -- hey, it was either that or the Cincinnati Reds, and Atlanta was closer. When I moved to Athens Gee-Ay in the late eighties, the last vestiges of the early eighties contenders had faded and the Atlanta dynasty was almost in place. We were all crazy for Braves baseball, crazy for the Olympics, crazy for the Atlanta renaissance that put the town on the map at the end of the twentieth century.

Skip's old-fashioned, slightly twisted, highly idiosyncratic radio calls took me through many a long road trip. I fell asleep to his voice whenever the Braves were on the West Coast. And thanks to TBS, I got him on TV too. For years the broadcasting teams would switch after four and a half innings -- the pair that started on TV moving to radio, and vice versa. It wasn't unusual for me to turn off the sound on the TV and follow Skip over to radio after half the game.

His immortal call of Francisco Cabrera's game-winning single and Sid Bream's lumbering trip home from second in Game 7 of the NLCS against the Pirates in 1992 -- "Here comes Bream! Here's the play at the plate! He is -- safe! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win!" -- was my System 7 startup sound for years afterward.

I was sad when Skip began to have less of a presence in my life and my continued Braves fandom, thanks to a move away from TBS broadcasting the Braves. I'm devastated that I'll never here him call a game again. Rest in peace.

We were always Braves fans in Chattanooga -- hey, it was either that or the Cincinnati Reds, and Atlanta was closer. When I moved to Athens Gee-Ay in the late eighties, the last vestiges of the early eighties contenders had faded and the Atlanta dynasty was almost in place. We were all crazy for Braves baseball, crazy for the Olympics, crazy for the Atlanta renaissance that put the town on the map at the end of the twentieth century.

Skip's old-fashioned, slightly twisted, highly idiosyncratic radio calls took me through many a long road trip. I fell asleep to his voice whenever the Braves were on the West Coast. And thanks to TBS, I got him on TV too. For years the broadcasting teams would switch after four and a half innings -- the pair that started on TV moving to radio, and vice versa. It wasn't unusual for me to turn off the sound on the TV and follow Skip over to radio after half the game.

His immortal call of Francisco Cabrera's game-winning single and Sid Bream's lumbering trip home from second in Game 7 of the NLCS against the Pirates in 1992 -- "Here comes Bream! Here's the play at the plate! He is -- safe! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win! Braves win!" -- was my System 7 startup sound for years afterward.

I was sad when Skip began to have less of a presence in my life and my continued Braves fandom, thanks to a move away from TBS broadcasting the Braves. I'm devastated that I'll never here him call a game again. Rest in peace.

Monday, June 23, 2008

How football and baseball are different

George Carlin was one of the fringe figures of my youth, relegated to furtive moments away from home. I remember sharing headphones with my friends on a glee club trip, listening to Carlin do his "place to put your stuff" routine, cackling and repeating the best lines.

He's been a part of my children's lives through his participation in Thomas The Tank Engine and Cars. I suppose it's a part of an entertainer's career evolution to take on these different kinds of roles late in life -- even ones that are diametrically opposed to his previous image. In time, transgressiveness mellows into nostalgia.

But of course Carlin had a mainstream appeal even during his edgiest days, appearing regularly on network television. It was his singular genius to remain committed to speaking frankly and not pulling punches, even as he became such a cultural fixture that just about anything funny that gets passed around via e-mail eventually gets his name attached to it.

Noel had the chance to interview him a couple of years ago. People often ask Noel whom he's interviewed lately, and while many of those names don't ring a bell with people over or under a certain age, when Noel mentioned Carlin everybody was impressed.

By the way, football is rigidly timed. Baseball -- we don't know when it's going to end! Maybe we'll have extra innings!

He's been a part of my children's lives through his participation in Thomas The Tank Engine and Cars. I suppose it's a part of an entertainer's career evolution to take on these different kinds of roles late in life -- even ones that are diametrically opposed to his previous image. In time, transgressiveness mellows into nostalgia.

But of course Carlin had a mainstream appeal even during his edgiest days, appearing regularly on network television. It was his singular genius to remain committed to speaking frankly and not pulling punches, even as he became such a cultural fixture that just about anything funny that gets passed around via e-mail eventually gets his name attached to it.

Noel had the chance to interview him a couple of years ago. People often ask Noel whom he's interviewed lately, and while many of those names don't ring a bell with people over or under a certain age, when Noel mentioned Carlin everybody was impressed.

By the way, football is rigidly timed. Baseball -- we don't know when it's going to end! Maybe we'll have extra innings!

Sunday, January 27, 2008

Requiescat in pace

Less than a week after Noel returned to us, he's off again -- and this time on a somber errand. His stepfather's father died last night after a short hospitalization. The memorial service is Wednesday in Nashville.

Alexander McDowell Smith, a retired stockbroker and an avid follower of the markets, was gracious enough to welcome me and our children into his extended family. He and his wife had no biological grandchildren, and so they embraced the children of their son's wife. They were generous always. I'm glad I got to know them in the years before illness began to claim their vitality.

Archer's middle name is Alexander, after Noel's stepfather, Alexander McDowell Smith, Jr. -- and therefore after his stepgrandfather as well. We were proud to carry on that name for them. This is a picture of the three generations of Alexanders, taken at Christmastime 2001. We'll miss you, Pops.

Alexander McDowell Smith, a retired stockbroker and an avid follower of the markets, was gracious enough to welcome me and our children into his extended family. He and his wife had no biological grandchildren, and so they embraced the children of their son's wife. They were generous always. I'm glad I got to know them in the years before illness began to claim their vitality.

Archer's middle name is Alexander, after Noel's stepfather, Alexander McDowell Smith, Jr. -- and therefore after his stepgrandfather as well. We were proud to carry on that name for them. This is a picture of the three generations of Alexanders, taken at Christmastime 2001. We'll miss you, Pops.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)