When we came into the restaurant, you were already there, a middle-aged woman in a booth across from two teenagers with their heads bent over a shared phone. We sat at a table nearby, not our usual spot, but the place was unusually crowded.

Archer was carrying on his usual lopsided conversation with his sister about videogames. I think he was talking about his plans for constructing a tournament in Mario Party 9 that we could all play together, with multiple boards over several days and a scoring system based on the ministars (or in the case of the Donkey Kong board, bananas) earned on each board.

Noel and I ordered and settled down to read the paper while Archer chattered away and Cady Gray gave the occasional response. Then you were suddenly standing by our table.

"I just wanted to tell you that your son reminds me so much of my son," you said. "My daughters noticed and were talking about it. My son is 21 and away at college."

"Just the way he's talking -- it's just like my boy," you said. I thought about mentioning the word "autism," but held back. There's no guarantee your son had a diagnosis. Maybe you just lived with his idiosyncrasies. Then you paused.

"Don't let anybody tell you ..." you said. Instantly we knew what you were trying to say. "Oh no, we would never," Noel said. "No, he's wonderful. We enjoy him so much," I said.

"Yes!" you exclaimed. "People don't understand how wonderful it can be." The waiter arrived with our food and you stepped back toward your booth. "Thank you so much," we said, and turned back to our meal.

When you left, as we were finishing up, you said "Take good care of that boy" and we all said thanks and goodbye. The waiter came to clear our table, and Noel asked for the check. "The lady at that table already paid," he said.

Lady at La Huerta, I wish I had asked about your son. One of the things we wonder about the most is what Archer might be like when he grows up. Your son must be doing well if he's away in college. I wish I knew more about him.

I know what it's like to recognize another autistic child in a public place. I sometimes want to say something, to empathize and make that connection, but I rarely do. It must have meant a lot to you, to do what you did. I wish I could tell you more about Archer, but maybe you saw everything you needed to see. You saw how his sister listens to him patiently. You saw how excited and articulate he is about what interests him. You saw how delighted he was to see something about March Madness on the TV, and to recite our March Madness motto: "Ten seconds is an eternity, dad."

Lady at La Huerta, you didn't look like you were noticeably wealthy. I'm sure $40 for our meal wasn't an insignificant expense for you. I apologize if I'm assuming too much, but I can't quite express all the ways your unprompted generosity touched me. The way you wanted to reach out, to show solidarity, to love your son by doing something nice for someone who reminded you of him -- it's so unexpected. And it seems to say everything about the experiences we probably share.

Conway is a small town. I'm sure we're not separated by six degrees; somebody I know knows somebody who knows you. Maybe this will make its way to you. I said "thank you" for your kind words when you passed by on your way out of the restaurant. If you see this, then I've got another chance: Thank you for much more, for your kind and generous actions. I hope that Archer grows up to be just like your son, and that I grow up to be just like you.

Friday, March 7, 2014

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Hail the Gatekeeper

Janus was the Roman god of transition. It's a strange thing to have a god for, at first glance. But anyone who's studied anthropology will recognize why he's needed. Any beginning or ending, any movement from one state to another, is fraught.

We've arrived at the annual moment where our culture recognizes this. And for me in particular, the transition into a new year, with its accompanying look back at 2013 and expression of hope for 2014, is an especially rich story of beginnings and endings.

I'm spending this last day of 2013 interviewing the 84th subject for my research into the prayer shawl ministry, and reviewing and tagging a transcript from one of my earlier interviews. It's hard to remember that eight months ago I had yet to do a single interview. I was nervously anticipating the inauguration of this new project, looking back with some regret at the phase of textual research -- a process I know how to do! -- that I was leaving behind for uncharted waters. One of the most unexpected rewards of this research has been learning that I am good at these qualitative interviews, and that when I'm doing them I am a better person -- a more empathetic person, a better listener, a more attentive and responsive dialogue partner. Another surprise: Just when I'm most concerned about how much I'm asking of those kind enough to agree to an interview, they tell me how much I've given to them, by prompting them to think, by valuing what they say and do, by opening a space for them to speak.

Now the trepidation moves to 2014, when I have to leave the data-gathering phase behind and produce the written analysis. I am optimistic, but still, the unknowns of the process are daunting.

In 2013, I started leaving behind the world of pop culture criticism that I have pursued, in some form or another, since college. I hit my high point in terms of audience and influence in the process of that exit, with my reviews of the last season of Breaking Bad for the A.V. Club. In 2014 I'll review the last 11 episodes of How I Met Your Mother and write an overview of the series for the A.V. Club's 100 Episodes feature. And then I'll be done.

I'm looking forward to exiting that grind and focusing on the grinds that are more directly related to my academic goals as a teacher and scholar. But I'll miss the push to reflect critically and to appreciate expansively. I'll miss the readers and the community of TV critics.

It's almost hard to remember how I fit it in, but the other thing I did last summer was compile a massive four-volume application for promotion to full professor. That rank represents the top of my profession. As of this moment the application has successfully wended its way through two committees and two administrative reviews, and awaits action in 2014 by the provost and the board of trustees. I expect to remove the "associate" from my title this spring, just in time to also remove the "dean."

I'll never get used to this process of looking back and forward. When I turn my gaze to the things already done or set in motion, I can't believe I found the time and energy. When I imagine what current efforts will look like when complete, I can't picture myself as the source and the agent. It's a pleasant shock, though, to glance back and be flummoxed by what you managed to accomplish, and to peek forward and get all excited about what it will feel like to glance back this time in 2014. I hope all of you are having similar feelings on this day -- Janus's Day Eve.

Sunday, December 22, 2013

The holly and the ivy

It's Christmastime in Conway, and a couple of times recently Noel has reminded me what we were doing at this time last year. The forecast showed a snowstorm bearing down on us, and for almost a week ahead of time, I fretted and made contingency plans for our planned drive to Nashville and flight to St. Simons. Eventually we made the decision to open presents on Christmas Eve and drive to Nashville on Christmas Day, mere hours ahead of the storm which ended up dumping nine inches of snow on our empty home.

The contrast with this year couldn't be greater. With no place to go, we are baking cookies, watching movies, crafting with the kids, and paying attention to the weather only with respect to the best time to make a grocery run. Noel's folks are arriving on Christmas Eve. I'll play handbells at the midnight service. And we'll open our presents on Christmas morning, as the baby Jesus intended.

I'm highly aware of my stress level these days. Many of the big decisions I made about my future this year were based on observation of what stresses me out in bad and good ways. Whole-family travel is a high-stress affair for me. I worry and make multiple levels of plans and try to keep everything as under control as possible. It's not something I should try to avoid in order to make my life more relaxed, of course (although to my shame, I do). But when I am not obligated to trek with everyone to some far-off destination -- especially on a tight schedule at symbolically-charged and heavily-trafficked cultural moments rendezvousing with multiple branches of the family, like at Christmas -- my quality of life shoots through the roof as my level of stress stays comfortably low.

As the years go by, the kids grow up, and the parents get older, each year's holiday planning is haunted by the shrinking number of opportunities it's using up. A chance to see the grandparents. A chance to establish and reinforce traditions. A chance to give. A chance to enjoy. A chance to worship. A chance to reflect. With every chance taken, exchanged, or passed up, a chunk of our family's life slides into memory.

I know everyone experiences these tradeoffs at this time of life. I wish I handled them with more grace, less self-absorption, more generosity, less anxiety. What you don't expect, I think, is that these phases of transition just keep coming at you, at times when you once thought that you'd be settled and finished with all that. And whatever choice you make, there's no way to completely avoid regret.

The contrast with this year couldn't be greater. With no place to go, we are baking cookies, watching movies, crafting with the kids, and paying attention to the weather only with respect to the best time to make a grocery run. Noel's folks are arriving on Christmas Eve. I'll play handbells at the midnight service. And we'll open our presents on Christmas morning, as the baby Jesus intended.

I'm highly aware of my stress level these days. Many of the big decisions I made about my future this year were based on observation of what stresses me out in bad and good ways. Whole-family travel is a high-stress affair for me. I worry and make multiple levels of plans and try to keep everything as under control as possible. It's not something I should try to avoid in order to make my life more relaxed, of course (although to my shame, I do). But when I am not obligated to trek with everyone to some far-off destination -- especially on a tight schedule at symbolically-charged and heavily-trafficked cultural moments rendezvousing with multiple branches of the family, like at Christmas -- my quality of life shoots through the roof as my level of stress stays comfortably low.

As the years go by, the kids grow up, and the parents get older, each year's holiday planning is haunted by the shrinking number of opportunities it's using up. A chance to see the grandparents. A chance to establish and reinforce traditions. A chance to give. A chance to enjoy. A chance to worship. A chance to reflect. With every chance taken, exchanged, or passed up, a chunk of our family's life slides into memory.

I know everyone experiences these tradeoffs at this time of life. I wish I handled them with more grace, less self-absorption, more generosity, less anxiety. What you don't expect, I think, is that these phases of transition just keep coming at you, at times when you once thought that you'd be settled and finished with all that. And whatever choice you make, there's no way to completely avoid regret.

Friday, November 22, 2013

Down the memory hole

I was listening to a podcast a few days ago, and the host made mocking mention of central vacuum systems. I don't remember the exact context, but the upshot was that the guests were asked if they lived in an early twentieth-century apartment building that had those outlets in the wall where you hooked up a hose and sucked dirt out of your life.

That's when I experience that sudden frisson of recognition, the kind that happens when a long-forgotten detail of your life swims up out of your memory, and you realize: I lived in a house that had those outlets.

When I was a kid, my family built a house on property we owned about twenty miles out of town. We moved to that house when I was in eighth grade. And that house had a central vacuum system. There were unobtrusive hinged wall plates in each room and along the hallways; you lifted the flap to find a hole. Plug a hose into that hole, attach the hose to a handle and the handle to a carpet sweeping head, and vacuum away. The dirt went into some collection device in the lower level of the house. I have vague memories that it was located in my dad's workshop, which was part of a small garage built to house his tractor, based on times when something that wasn't supposed to be vacuumed was, necessitating some foraging around in the collection bin to retrieve it.

Those wall plates fascinated me. The whole system did, really. Vacuuming was one of the more pleasant chores I was occasionally assigned, because I could use it. Was the suction always on? When you lifted the lid, it didn't seem to resist you, but when you removed the hose and flipped the lid down, it seemed to get sucked into place. Were there switches built into the lid mechanisms somehow that triggered the suction?

And then there were the holes themselves. They were tempting to a curious child in the way all openings to mysterious places seem to be. What would happen if I put a ping-pong ball or a Christmas ornament in there? The hose obscured what would surely be fascinating to witness directly, the sight of an item suddenly being whisked away, popped out of your hands like a message in a pneumatic tube.

I've never encountered another house with one of these systems, but I see online that they're marketed to residential customers. I had no idea until hearing the podcast that they were associated with a certain era of multifamily housing in the minds of some urbanites. I kinda wish my current house had one. Maybe I'd even vacuum once in a while.

That's when I experience that sudden frisson of recognition, the kind that happens when a long-forgotten detail of your life swims up out of your memory, and you realize: I lived in a house that had those outlets.

When I was a kid, my family built a house on property we owned about twenty miles out of town. We moved to that house when I was in eighth grade. And that house had a central vacuum system. There were unobtrusive hinged wall plates in each room and along the hallways; you lifted the flap to find a hole. Plug a hose into that hole, attach the hose to a handle and the handle to a carpet sweeping head, and vacuum away. The dirt went into some collection device in the lower level of the house. I have vague memories that it was located in my dad's workshop, which was part of a small garage built to house his tractor, based on times when something that wasn't supposed to be vacuumed was, necessitating some foraging around in the collection bin to retrieve it.

Those wall plates fascinated me. The whole system did, really. Vacuuming was one of the more pleasant chores I was occasionally assigned, because I could use it. Was the suction always on? When you lifted the lid, it didn't seem to resist you, but when you removed the hose and flipped the lid down, it seemed to get sucked into place. Were there switches built into the lid mechanisms somehow that triggered the suction?

And then there were the holes themselves. They were tempting to a curious child in the way all openings to mysterious places seem to be. What would happen if I put a ping-pong ball or a Christmas ornament in there? The hose obscured what would surely be fascinating to witness directly, the sight of an item suddenly being whisked away, popped out of your hands like a message in a pneumatic tube.

I've never encountered another house with one of these systems, but I see online that they're marketed to residential customers. I had no idea until hearing the podcast that they were associated with a certain era of multifamily housing in the minds of some urbanites. I kinda wish my current house had one. Maybe I'd even vacuum once in a while.

Sunday, November 17, 2013

Use it up, wear it out

When I step down from administration in a couple of months, I'll be taking a pay cut. That wasn't the hardest part of contemplating the decision, strangely enough. But it's a somewhat unprecedented event in my career. I've actually been very lucky in the past five years; faculty at many institutions lost their jobs or had their pay slashed or benefits cut during the recession, and all that happened to me and my colleagues was no raises. (Which actually dated to years before the recession because of financial mismanagement, so we were used to it.) So facing a future with fewer dollars in the paycheck isn't something I really know how to do.

It's spooked me a little. There's no logical reason for this. We're just a few mortgage payments away from being completely debt-free, and we have plenty of resources to draw upon in case of need. But I'm used to having more than enough, and those resources aren't currently liquid.

So right now I'm holding off on some purchases that, to be frank, would be smarter to make today. Since before we renovated the kitchen, our decades-old washing machine has been steadily deteriorating. Currently the wash selector knob is held together with duct tape, and the push-pull functionality that stops the cycle no longer works. So when it buzzes for an unbalanced load, I can't pull to stop it and rearrange the clothes; I have to turn it past the spin cycle and rearrange while it's filling or draining or whatever, a disconcerting race against time until I can turn it all the way back around to spin. And after the kitchen was finished and we put the dryer back in the laundry room, it's never worked right; the air doesn't seem to blow on most cycles, and I have to put it on high heat to get any drying at all. It takes three or four cycles to get a load of clothes dry. Given that and given the age of the washer, I'm throwing money down the drain every time I use them. But the new washer and dryer I want are expensive, and there's that pay cut looming. I can't afford to keep using these, but it's scary to contemplate the hit on the checking account from a huge purchase, given how slowly that account is recovering from the renovation costs, and how much more slowly it will grow once the new year starts and my paychecks are smaller by almost twenty percent.

If that were all ... but it's not, of course. We know that our wonderful plasma TV is on its last legs. I've needed a new Macbook for some time. Each of those purchases, if we did them right, would be four figures. We could do them cheaper, of course, but I resist that solution. You'd be amazed at how much of my happiness is bound up in things that work right and do what they're supposed to, and how much of my joy is sapped, on a daily basis, by things that don't. If we're going to replace stuff, I want to invest in the good stuff, not the as-good-as-we-can-afford stuff.

So ironically, I keep on making do with stuff that barely works at all. The great, in this case, is the enemy of the good. My comfort level with spending a lot of money has never been high, but I could always talk myself into it when I knew from experience that my account balance would bounce back within a few months, and when I knew what I wanted. Now I have an additional mental barrier: the uncertainty of what it will feel like to have less money coming in. It's not an objectively significant problem, compared to people who have actual financial issues. It's just my personal problem, rooted in my personal emotional history with money. But there it is, nagging at me every time I walk back to the dryer, check to see if the clothes are still damp, and start another cycle.

It's spooked me a little. There's no logical reason for this. We're just a few mortgage payments away from being completely debt-free, and we have plenty of resources to draw upon in case of need. But I'm used to having more than enough, and those resources aren't currently liquid.

So right now I'm holding off on some purchases that, to be frank, would be smarter to make today. Since before we renovated the kitchen, our decades-old washing machine has been steadily deteriorating. Currently the wash selector knob is held together with duct tape, and the push-pull functionality that stops the cycle no longer works. So when it buzzes for an unbalanced load, I can't pull to stop it and rearrange the clothes; I have to turn it past the spin cycle and rearrange while it's filling or draining or whatever, a disconcerting race against time until I can turn it all the way back around to spin. And after the kitchen was finished and we put the dryer back in the laundry room, it's never worked right; the air doesn't seem to blow on most cycles, and I have to put it on high heat to get any drying at all. It takes three or four cycles to get a load of clothes dry. Given that and given the age of the washer, I'm throwing money down the drain every time I use them. But the new washer and dryer I want are expensive, and there's that pay cut looming. I can't afford to keep using these, but it's scary to contemplate the hit on the checking account from a huge purchase, given how slowly that account is recovering from the renovation costs, and how much more slowly it will grow once the new year starts and my paychecks are smaller by almost twenty percent.

If that were all ... but it's not, of course. We know that our wonderful plasma TV is on its last legs. I've needed a new Macbook for some time. Each of those purchases, if we did them right, would be four figures. We could do them cheaper, of course, but I resist that solution. You'd be amazed at how much of my happiness is bound up in things that work right and do what they're supposed to, and how much of my joy is sapped, on a daily basis, by things that don't. If we're going to replace stuff, I want to invest in the good stuff, not the as-good-as-we-can-afford stuff.

So ironically, I keep on making do with stuff that barely works at all. The great, in this case, is the enemy of the good. My comfort level with spending a lot of money has never been high, but I could always talk myself into it when I knew from experience that my account balance would bounce back within a few months, and when I knew what I wanted. Now I have an additional mental barrier: the uncertainty of what it will feel like to have less money coming in. It's not an objectively significant problem, compared to people who have actual financial issues. It's just my personal problem, rooted in my personal emotional history with money. But there it is, nagging at me every time I walk back to the dryer, check to see if the clothes are still damp, and start another cycle.

Saturday, November 9, 2013

A city that the damned call home

This year I've cut way back on my conference travel. Ordinarily this time of year I'd be juggling presentations and meetings at the national Honors education meeting, followed closely by the American Academy of Religion. But following my exit from most official posts at these organizations, I'm strangely passive about their yearly demands to gather in vibrant cities at big hotels and attend multiple parties. Back in the distant spring, before I made the decision to step down from administration, my boss included me as co-presenter on a session for this year's National Collegiate Honors Society meeting in New Orleans, so I've known for quite some time I would attend. But I've been otherwise content just to let it happen, and hope someone would tell me where to show up. (That's almost too much to expect, it seems; I somehow got left off the list of recipients when the big conference agenda was shared, so I didn't even know when our group dinner was until my boss happened to mention it earlier that day.)

The lack of business suits my mood -- and the mood of the city. I attend some sessions, do some thinking, grab a couple of hours off site to sample the city's food (from beignets to po'boys to gumbo), and try not to add to the self-important bustle of the conference. I support my colleagues and get a little work done and have the football game playing in my shared hotel room by 8:30 pm. And occasionally I wonder: Do I miss being at the center of the action? Having a bunch of special ribbons on my nametag? (The NCHC is crazy for one-off ribbons; there are at least a dozen that I've seen that only one attendee is entitled to wear.) I note that some of the decisions and work are quite important, not only to the organization and its members, but quite literally in the sphere of life and death. But of course, removed from that context as I am, it is undeniably pleasant to leave the worrying and the detail-obsessions to someone else.

This will be the first time I haven't been at the American Academy of Religion annual meeting in many, many years. I believe the last one I missed was probably 1997. I went when my children were babes in arms, I went when I had interviews, I went when I had papers to give, and for the last six years, I went as a member of the board of directors. This year I have no committees to staff and I have no papers to give, so there was no rationale for me to ask for my department's support with travel expenses. I let it go. I'll miss it when my friends post to Facebook or tweet about the meeting, but I doubt I will spend a lot of time feeling left out. I have plenty on my plate.

But I confess that sitting in a business meeting here at NCHC this morning, my mind wandered to the AAR office I told many people I might run for in the future. I thought I might do it sooner rather than later. A year out of the trenches and away from the social whirl feels like a vacation. Two years, a well-earned sabbatical. When it starts getting to be a habit, though, you might start feeling sidelined. Irrelevent. Give me a chance to recuperate a bit longer, and then if you have a committee that needs a member or an office that needs a candidate, call me. I don't want to need that kind of status; I hope I'm beyond ever needing to feel important. And I'm way past wanting to have people pile responsibilities on me just so I can stay at the center of things. But on my own terms? I could see it happening again. And I'm betting it will feel as different as night and day, after having climbed the ladder once and been truly grateful to step off the rungs back to solid ground.

The lack of business suits my mood -- and the mood of the city. I attend some sessions, do some thinking, grab a couple of hours off site to sample the city's food (from beignets to po'boys to gumbo), and try not to add to the self-important bustle of the conference. I support my colleagues and get a little work done and have the football game playing in my shared hotel room by 8:30 pm. And occasionally I wonder: Do I miss being at the center of the action? Having a bunch of special ribbons on my nametag? (The NCHC is crazy for one-off ribbons; there are at least a dozen that I've seen that only one attendee is entitled to wear.) I note that some of the decisions and work are quite important, not only to the organization and its members, but quite literally in the sphere of life and death. But of course, removed from that context as I am, it is undeniably pleasant to leave the worrying and the detail-obsessions to someone else.

This will be the first time I haven't been at the American Academy of Religion annual meeting in many, many years. I believe the last one I missed was probably 1997. I went when my children were babes in arms, I went when I had interviews, I went when I had papers to give, and for the last six years, I went as a member of the board of directors. This year I have no committees to staff and I have no papers to give, so there was no rationale for me to ask for my department's support with travel expenses. I let it go. I'll miss it when my friends post to Facebook or tweet about the meeting, but I doubt I will spend a lot of time feeling left out. I have plenty on my plate.

But I confess that sitting in a business meeting here at NCHC this morning, my mind wandered to the AAR office I told many people I might run for in the future. I thought I might do it sooner rather than later. A year out of the trenches and away from the social whirl feels like a vacation. Two years, a well-earned sabbatical. When it starts getting to be a habit, though, you might start feeling sidelined. Irrelevent. Give me a chance to recuperate a bit longer, and then if you have a committee that needs a member or an office that needs a candidate, call me. I don't want to need that kind of status; I hope I'm beyond ever needing to feel important. And I'm way past wanting to have people pile responsibilities on me just so I can stay at the center of things. But on my own terms? I could see it happening again. And I'm betting it will feel as different as night and day, after having climbed the ladder once and been truly grateful to step off the rungs back to solid ground.

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Radio on

I'll bet a lot of people who know me well think of me as an early adopter. I enjoy new technology, I like to try new ways of doing things, and figuring out how to integrate new processes into my life and work. I tend to be enthusiastic about innovation.

So it's got to be a little confusing to those people that some of the commonplace technologies of the last five or ten years are things that I've only recently, maybe even reluctantly, adopted. I've told many people the story of how I finally started carrying a cell phone only three or four years ago, fully a decade after most people in my shoes had become tethered to them. Some people wear their refusal to give in to cell phones or some other type of networking or availability technology as a badge of pride. Me, I'm embarrassed at how long it took me to join in. I inconvenienced everyone else for years because of my belief that I was different, that there was no need for me to be like them.

Similarly, I heard my friends talking about listening to podcasts for years and years. They'd talk about the ones they enjoyed, the ones they learned from, the ones that they follow week after week. And although I understood the concept, and I've had an iPod since they were invented, I never thought they were for me. When did people listen to these things? I didn't have a commute. When I exercised, I needed energetic music, not people talking. If I tried to listen to something other than music while working, I lose the thread of it, and suddenly I remember to listen and I have no idea what they're talking about. When else could I put on headphones and listen to some program? It would take time that I would rather use for doing other things, for writing or reading or watching something, none of which I can do while listening to a podcast.

The moment that changed was last year, when I decided I need to stop running. I had injured myself a couple of times, and the effort of pushing past that pain to keep on doing something I really didn't enjoy that much, just didn't seem worth it. I couldn't seem to break through the plateau and lose any more weight, or get any noticeable increase in endurance or speed. At the same time, I had known for years that I needed to find a way to integrate strength training into my life, but because just getting through the cardio was so time-consuming and took so much willpower, I couldn't stomach adding a whole other regimen on top of it.

What I decided to do was replace running with walking, and to do my walking in a practical fashion. Instead of walking around a track or around town, for exercise only, I would walk to places I needed to go anyway. Then my workout time could be devoted to weight training.

So I started walking Cady Gray to school, a thirty-minute round trip. On the way there we talk together, but on my way back, I'm alone. Then frequently I pick up my satchel and head on to my office, another fifteen minutes. When I go to the gym, I don't need uptempo music in the weight room. You lift for a minute or two, and then you rest. There's a lot of downtime.

And that's when I started listening to podcasts. And because they're stories, I didn't want to just turn them off when I'm done with the walk or the workout. I turn on the speaker to my phone, or hook them up to the stereo in the car, and keep listening while I run errands, or walk from one side of campus to the other. Podcast listening went from no part of my life, to seeping into more and more parts of my life from the gym and the sidewalk where they started.

There's nothing more annoying that the person who just got into something trying to tell you all about that thing. I'm just scratching the surface of the world of podcasts. What I really like about them, though, is that essentially they're radio on your time rather than broadcast time. I've always loved radio. (Maybe that's another post.) When DVRs came around for TV, I wondered whether such a thing would ever be possible for radio, and I felt a little pang to think that nobody would spend time building anything like that for what was considered a moribund medium. But now I understand. The energy to make radio timeshiftable and portable went in a different direction than the DVR, one that's not as closely tied to the continuous, clockbound nature of broadcast radio. People are making more radio than ever. I'm glad I figured out how to fit it into my life.

So it's got to be a little confusing to those people that some of the commonplace technologies of the last five or ten years are things that I've only recently, maybe even reluctantly, adopted. I've told many people the story of how I finally started carrying a cell phone only three or four years ago, fully a decade after most people in my shoes had become tethered to them. Some people wear their refusal to give in to cell phones or some other type of networking or availability technology as a badge of pride. Me, I'm embarrassed at how long it took me to join in. I inconvenienced everyone else for years because of my belief that I was different, that there was no need for me to be like them.

Similarly, I heard my friends talking about listening to podcasts for years and years. They'd talk about the ones they enjoyed, the ones they learned from, the ones that they follow week after week. And although I understood the concept, and I've had an iPod since they were invented, I never thought they were for me. When did people listen to these things? I didn't have a commute. When I exercised, I needed energetic music, not people talking. If I tried to listen to something other than music while working, I lose the thread of it, and suddenly I remember to listen and I have no idea what they're talking about. When else could I put on headphones and listen to some program? It would take time that I would rather use for doing other things, for writing or reading or watching something, none of which I can do while listening to a podcast.

The moment that changed was last year, when I decided I need to stop running. I had injured myself a couple of times, and the effort of pushing past that pain to keep on doing something I really didn't enjoy that much, just didn't seem worth it. I couldn't seem to break through the plateau and lose any more weight, or get any noticeable increase in endurance or speed. At the same time, I had known for years that I needed to find a way to integrate strength training into my life, but because just getting through the cardio was so time-consuming and took so much willpower, I couldn't stomach adding a whole other regimen on top of it.

What I decided to do was replace running with walking, and to do my walking in a practical fashion. Instead of walking around a track or around town, for exercise only, I would walk to places I needed to go anyway. Then my workout time could be devoted to weight training.

So I started walking Cady Gray to school, a thirty-minute round trip. On the way there we talk together, but on my way back, I'm alone. Then frequently I pick up my satchel and head on to my office, another fifteen minutes. When I go to the gym, I don't need uptempo music in the weight room. You lift for a minute or two, and then you rest. There's a lot of downtime.

And that's when I started listening to podcasts. And because they're stories, I didn't want to just turn them off when I'm done with the walk or the workout. I turn on the speaker to my phone, or hook them up to the stereo in the car, and keep listening while I run errands, or walk from one side of campus to the other. Podcast listening went from no part of my life, to seeping into more and more parts of my life from the gym and the sidewalk where they started.

There's nothing more annoying that the person who just got into something trying to tell you all about that thing. I'm just scratching the surface of the world of podcasts. What I really like about them, though, is that essentially they're radio on your time rather than broadcast time. I've always loved radio. (Maybe that's another post.) When DVRs came around for TV, I wondered whether such a thing would ever be possible for radio, and I felt a little pang to think that nobody would spend time building anything like that for what was considered a moribund medium. But now I understand. The energy to make radio timeshiftable and portable went in a different direction than the DVR, one that's not as closely tied to the continuous, clockbound nature of broadcast radio. People are making more radio than ever. I'm glad I figured out how to fit it into my life.

Sunday, October 13, 2013

One voice

Yesterday was our seventeenth wedding anniversary. I got Noel a new phone. He got me (in addition to some book that hasn't appeared yet, but hey, I'm not going to be the first to bring it up) a day alone with my daughter while he went along with Archer to the All-Region Choir tryouts.

I sang in choirs throughout my childhood. But I never competed for a spot in any of these mass choirs. My elementary school didn't have a choir or an orchestra, and my secondary school didn't participate in whatever organization oversees these things. So this whole world of honor choirs and orchestras and bands and cheer squads and who knows what all is completely new to me.

I do know the choir world well, though. I know the music and the rehearsals and the participants. And I was hopeful, when we chose Archer's electives for this seventh grade year, that he would get into it. He is fascinated by the technical side of music -- notation, theory, structure -- and he has perfect pitch. I didn't know if he'd like the process of learning, rehearsing, and performing. But his teacher (who also leads the music programs at our church) says that he's a classroom leader, grasping the music quickly and helping others to get it and stay on track.

Noel followed the school bus up to Clarksville on Saturday, and stayed with Archer while waiting for his group to be called and to make their way in stages back to the audition rooms. It was hard for us to imagine what Archer would do with the long, long of waiting. I'm still nervous about sending him off into unstructured situations, where there's no one around who can keep an eye on him. He almost certainly would handled it fine. Without some firsthand experience of the setup, though, there was no way for us to know that.

It's reportedly unusual for first-timers to make the grade in these auditions. When I asked Archer to rate his performance, he reported that he would give it a 98%. For the last couple of weeks, he's been telling us about the pieces they chose, what key they're in, how many vocal parts, their suggested tempo in beats per minute, the song structure. He seems positive about the whole experience. I wouldn't be at all disappointed if choir became one of his things, like it was always one of mine.

I sang in choirs throughout my childhood. But I never competed for a spot in any of these mass choirs. My elementary school didn't have a choir or an orchestra, and my secondary school didn't participate in whatever organization oversees these things. So this whole world of honor choirs and orchestras and bands and cheer squads and who knows what all is completely new to me.

I do know the choir world well, though. I know the music and the rehearsals and the participants. And I was hopeful, when we chose Archer's electives for this seventh grade year, that he would get into it. He is fascinated by the technical side of music -- notation, theory, structure -- and he has perfect pitch. I didn't know if he'd like the process of learning, rehearsing, and performing. But his teacher (who also leads the music programs at our church) says that he's a classroom leader, grasping the music quickly and helping others to get it and stay on track.

Noel followed the school bus up to Clarksville on Saturday, and stayed with Archer while waiting for his group to be called and to make their way in stages back to the audition rooms. It was hard for us to imagine what Archer would do with the long, long of waiting. I'm still nervous about sending him off into unstructured situations, where there's no one around who can keep an eye on him. He almost certainly would handled it fine. Without some firsthand experience of the setup, though, there was no way for us to know that.

It's reportedly unusual for first-timers to make the grade in these auditions. When I asked Archer to rate his performance, he reported that he would give it a 98%. For the last couple of weeks, he's been telling us about the pieces they chose, what key they're in, how many vocal parts, their suggested tempo in beats per minute, the song structure. He seems positive about the whole experience. I wouldn't be at all disappointed if choir became one of his things, like it was always one of mine.

Thursday, October 10, 2013

Shuffling in the dark

For the past three years, I've run a short race on our campus called "Trick Or Trot." As you might gather, it's Halloween themed; costumes are encouraged but thankfully, not required.

This year I signed up even though I haven't run hardly a step in over a year. I stopped running because (a) I really hate running (although I love having run), and (b) I felt like I was destroying what was left of my knees and ankles every time I pounded around the track. In place of my slow, painful jog, I joined many people many age in walking. I racked up as many miles, or more, by walking my daughter to school and walking myself to work, as I used to accumulate at the gym. I took up weightlifting, too, and experienced that gratifying surge of strength, so quantifiable by the heavier and heavier plates you can pile onto the bar.

So why sign up for Trick Or Trot? The most simple reason is that I don't want to break the streak. Not signing up feels like capitulating to age. And I don't have to run; a lot of people walk the short two-mile circuit around campus after dark, peppered with glowstick-waving volunteers and cheerleaders.

But I'd like to run. Here's where I'm at with running: I'd like to think I could crank out a slow, steady mile or two even though I haven't done it in a year. Even though the thought of actually training to run is unbearable. I'd like to see how much I'm fooling myself with that notion.

So I'll line up at the back with the walkers, and I'll jog as far as I can go, and then the moment will come that I consider walking. It might be after a hundred yards, or after half a mile. Maybe I'll astound myself and be able to press on farther. But at some point I'll find out just how thin a soap bubble my abandoned veneer of "runner" really is. How long can I pretend, and what will I think of myself when I can't pretend any longer? Oh, I'll finish, walking, jogging, or crawling. I'll start my 49th year with a new t-shirt and a feeling of accomplishment. The question is whether that accomplishment will be a pleasant surprise, or a salvage job.

Update: I ran about 1.1 miles before walking, and only walked two stretches. A very pleasant surprise!

This year I signed up even though I haven't run hardly a step in over a year. I stopped running because (a) I really hate running (although I love having run), and (b) I felt like I was destroying what was left of my knees and ankles every time I pounded around the track. In place of my slow, painful jog, I joined many people many age in walking. I racked up as many miles, or more, by walking my daughter to school and walking myself to work, as I used to accumulate at the gym. I took up weightlifting, too, and experienced that gratifying surge of strength, so quantifiable by the heavier and heavier plates you can pile onto the bar.

So why sign up for Trick Or Trot? The most simple reason is that I don't want to break the streak. Not signing up feels like capitulating to age. And I don't have to run; a lot of people walk the short two-mile circuit around campus after dark, peppered with glowstick-waving volunteers and cheerleaders.

But I'd like to run. Here's where I'm at with running: I'd like to think I could crank out a slow, steady mile or two even though I haven't done it in a year. Even though the thought of actually training to run is unbearable. I'd like to see how much I'm fooling myself with that notion.

So I'll line up at the back with the walkers, and I'll jog as far as I can go, and then the moment will come that I consider walking. It might be after a hundred yards, or after half a mile. Maybe I'll astound myself and be able to press on farther. But at some point I'll find out just how thin a soap bubble my abandoned veneer of "runner" really is. How long can I pretend, and what will I think of myself when I can't pretend any longer? Oh, I'll finish, walking, jogging, or crawling. I'll start my 49th year with a new t-shirt and a feeling of accomplishment. The question is whether that accomplishment will be a pleasant surprise, or a salvage job.

Update: I ran about 1.1 miles before walking, and only walked two stretches. A very pleasant surprise!

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

A new season

Tomorrow I turn 48 years old. You know, as long as there's a four in that tens column, I still feel young. And in two years when that changes, I'll probably feel young anyway.

I haven't written much in the last year. A post a quarter, maybe two. It's because I've been busy, of course; in my down moments I haven't felt like doing much other than knitting, sitting, watching TV, hugging my daughter. But it's also because this past year has been All About Me, and even though this is my blog, I've never been comfortable treating it as a therapist's couch. I haven't wanted to show up every few days and repeat the same stuff about my mid-life crisis.

But you know what? I think that's finally over. I made the decision to leave administration, and despite some lingering backward glances at the extra money, I'm happy about that every day. I couldn't be prouder of Noel and the awesome work he's doing at his brand new publication. I'm bringing to a close a period in my life where I practiced weekly television criticism, and reclaiming those evenings as time to do something other than work. And I've gotten an immense, humbling outpouring of praise for that work as the series I cover come to a close -- a thousand times more readers than I ever could have imagined, and hundreds of people saying nice things about what the work has meant to them. My promotion application for full professor is making its way up the chain of command. I've even gotten a couple of recent invitations to speak at conferences, related both to my theological work and my criticism. My research excites me, my book is underway, and there's a stack of other projects I hope to get to someday. It feels very much like I've made it to where I wanted to be when I started out.

Maybe it's the end of weekly writing about television that has prompted me to come back here. I've learned a lot about writing from blogging every day for years; I put much of it to use writing on short deadlines two and three times a week. I wouldn't like to see those muscles atrophy. (I'll need them for all the books I have to write.)

And while I've been away, my kids have been growing. I love to write about my kids. They are endlessly fascinating. People tell me they like to read about my kids -- well, about Archer particularly. He's done amazing things while I've been writing elsewhere. I don't want to miss the chance to get the stories down, and to share them. (I'm inspired here by amonthofson.com, Matthew Baldwin's lovely project about how his classically-autistic boy interacts with the world.)

So let's see if we can meet here more often, shall we? Teaching, writing, television, kids, theology, movies, sports, and the occasional self-indulgent state-of-the-Donna report. Hope it turns out well for all of us.

I haven't written much in the last year. A post a quarter, maybe two. It's because I've been busy, of course; in my down moments I haven't felt like doing much other than knitting, sitting, watching TV, hugging my daughter. But it's also because this past year has been All About Me, and even though this is my blog, I've never been comfortable treating it as a therapist's couch. I haven't wanted to show up every few days and repeat the same stuff about my mid-life crisis.

But you know what? I think that's finally over. I made the decision to leave administration, and despite some lingering backward glances at the extra money, I'm happy about that every day. I couldn't be prouder of Noel and the awesome work he's doing at his brand new publication. I'm bringing to a close a period in my life where I practiced weekly television criticism, and reclaiming those evenings as time to do something other than work. And I've gotten an immense, humbling outpouring of praise for that work as the series I cover come to a close -- a thousand times more readers than I ever could have imagined, and hundreds of people saying nice things about what the work has meant to them. My promotion application for full professor is making its way up the chain of command. I've even gotten a couple of recent invitations to speak at conferences, related both to my theological work and my criticism. My research excites me, my book is underway, and there's a stack of other projects I hope to get to someday. It feels very much like I've made it to where I wanted to be when I started out.

Maybe it's the end of weekly writing about television that has prompted me to come back here. I've learned a lot about writing from blogging every day for years; I put much of it to use writing on short deadlines two and three times a week. I wouldn't like to see those muscles atrophy. (I'll need them for all the books I have to write.)

And while I've been away, my kids have been growing. I love to write about my kids. They are endlessly fascinating. People tell me they like to read about my kids -- well, about Archer particularly. He's done amazing things while I've been writing elsewhere. I don't want to miss the chance to get the stories down, and to share them. (I'm inspired here by amonthofson.com, Matthew Baldwin's lovely project about how his classically-autistic boy interacts with the world.)

So let's see if we can meet here more often, shall we? Teaching, writing, television, kids, theology, movies, sports, and the occasional self-indulgent state-of-the-Donna report. Hope it turns out well for all of us.

Labels:

blogging,

criticism,

kids,

midlife crisis,

television,

writing

Saturday, August 17, 2013

Commencement

You can't say that the end of summer sneaked up on me. I've had an eye on the calendar ever since the beginning of July, when I came home from my second research trip and took stock of the last half of my sabbatical. The kids bought their school supplies two weeks ago. U-Hauls are stacked up in front of the dorms at my campus across the street, and tomorrow the flood of new first-years will be arriving.

I walked through the Jewel Moore Nature Reserve with Archer and Cady Gray this afternoon, taking advantage of the incredibly cool weather we've had this summer; where normally temperatures would be pushing or exceeding 100 in August, it's in the low 80's at the moment. As I strolled along and listened to them discuss Pokemon and the deer and rabbit tracks they saw on the trail, I was suddenly struck by a contrast. Frequently last year I came to the Nature Reserve in a desperate attempt to de-stress. The knots in my back and shoulders, the uncertainty, the sense of my life being beyond my control -- I returned to this place again and again, searching for an escape.

Today on the eve of the new academic year beginning, I felt no stress. The magic I was looking for, I found in time away from my administrative load, and time spent thinking deeply about theology. Having made the decision to return to full-time teaching and research, I shed my last remaining doubts more quickly than I expected. Almost without my noticing, my future acquired a shape I recognized. The vague vertigo of an escalator carrying me somewhere I didn't want to go -- it was gone, replaced by a confidence that whatever happened next, I could handle it.

It's amazing how that shift has carried over into other parts of my life. The kids are growing up, and there are plenty of things to worry about there. But I've never been so confident that they're well equipped and poised for success. I know they have challenges coming. But when those hurdles aren't added on to obstacles in my own life, they seem far less terrifying.

When I stop to think about it too long, I can find plenty to fret about. I'm a natural at worrying. But one thing that doesn't concern me is whether I've made the right choice. This summer hasn't just changed my career trajectory. It's changed -- or reset -- my definition of doing well. Success doesn't mean more money and more titles and more people to supervise. It means converting a lifetime of the learning I care about into the lessons that give students more power over their pasts, presents, and futures.

I can't wait to get started.

I walked through the Jewel Moore Nature Reserve with Archer and Cady Gray this afternoon, taking advantage of the incredibly cool weather we've had this summer; where normally temperatures would be pushing or exceeding 100 in August, it's in the low 80's at the moment. As I strolled along and listened to them discuss Pokemon and the deer and rabbit tracks they saw on the trail, I was suddenly struck by a contrast. Frequently last year I came to the Nature Reserve in a desperate attempt to de-stress. The knots in my back and shoulders, the uncertainty, the sense of my life being beyond my control -- I returned to this place again and again, searching for an escape.

Today on the eve of the new academic year beginning, I felt no stress. The magic I was looking for, I found in time away from my administrative load, and time spent thinking deeply about theology. Having made the decision to return to full-time teaching and research, I shed my last remaining doubts more quickly than I expected. Almost without my noticing, my future acquired a shape I recognized. The vague vertigo of an escalator carrying me somewhere I didn't want to go -- it was gone, replaced by a confidence that whatever happened next, I could handle it.

It's amazing how that shift has carried over into other parts of my life. The kids are growing up, and there are plenty of things to worry about there. But I've never been so confident that they're well equipped and poised for success. I know they have challenges coming. But when those hurdles aren't added on to obstacles in my own life, they seem far less terrifying.

When I stop to think about it too long, I can find plenty to fret about. I'm a natural at worrying. But one thing that doesn't concern me is whether I've made the right choice. This summer hasn't just changed my career trajectory. It's changed -- or reset -- my definition of doing well. Success doesn't mean more money and more titles and more people to supervise. It means converting a lifetime of the learning I care about into the lessons that give students more power over their pasts, presents, and futures.

I can't wait to get started.

Sunday, July 7, 2013

Changing course

I am halfway through so many things. Halfway through my sabbatical. Halfway through my academic career. Halfway through my life (if I am fortunate). Halfway through raising my children.

Our family has always rendered the old saying this way: Don't change horses in midstream. I don't know if that's the original or some muddle of horses and boats. But I know what it means. If you get cold feet about whether your original strategy is working out, think twice before trying to change it, lest you wind up in the drink.

But like all such bits of folksy advice, it's difficult to know when it applies. Sticking to the wrong methodology just because you fear it might be too late to make a change -- that's not a good idea either. There's wisdom in recognizing when you have made a wrong start, even if you are already halfway through the course.

There's a lot to be said for administration. A good administrator is a tremendous benefit to an organization. Administrators at their best can build structures where wonderful things happen, can reward people who do them, can obtain resources for them, can clarify procedures and expectations so that people know how to get things done, can provide evidence to demonstrate the wonderful things happening.

I know that I want to work for good administrators, and I know that I've been very fortunate to work for them and learn from them. (The bad ones have taught me some important lessons, too.) But at least where I am now, here at the halfway point, I want to get off the administrative horse.

It's carrying me farther away from teaching, farther away from being a productive scholar. What it's carrying me towards is something that needs to be done, but it's not something I need to do. As a person who likes to be in full control of everything, whether it's any of my business of not, recognizing the difference between "a job that needs to be done well" and "my job" has always been difficult for me. Here halfway through, I have to remind myself that caring about something does not require managing or leading it.

I've received a lot of great advice about this halfway point from relative strangers and from people who know me well. Most of it is simple and obvious, but rings almost heartbreakingly true. Just because you are good at something does not mean it's what you ought to do. You can't be there for the people you care about unless you take care of yourself. Arrange your life to spend the bulk of your time on what's most important.

It's been hard to accept the conclusions that are inescapable when I follow that advice, because I've spend so much time riding this horse to the middle of the stream. But it would be more foolish to stay on this horse than to attempt a change, however risky.

When I entered academia, I wanted to help students mature in their thinking about religion. I've done less and less of that each year. It's no less needed than fifteen years ago; quite the opposite. It would be a personal failure, and a terrible shame, if I let go of that goal when I have the ability and the position to accomplish it. And focusing on what's important to me will allow me to reclaim the energy that administrative tasks tend to drain away. The thought of doing more of the latter in the future is bleak and dispiriting; the thought of teaching the subjects about which I'm passionate, of reading, researching, and writing in the field where I can contribute something unique, is exciting. The message couldn't be more clear.

That's where I stand, halfway through. Changing horses and changing courses is a process. I'm not where I was in this process of rethinking and reorienting six months ago, but if you'd asked me then where I thought I was going, I should have told you, if I were being honest, that I suspected I might end up here. I might have feared it more than anticipated it then. Now the fear is diminishing.

Maybe I've been on the other horse for awhile, and just needed to open my eyes to see which way I've been headed. Check back in a few months and see if I've picked up the reins or have been swept away.

Our family has always rendered the old saying this way: Don't change horses in midstream. I don't know if that's the original or some muddle of horses and boats. But I know what it means. If you get cold feet about whether your original strategy is working out, think twice before trying to change it, lest you wind up in the drink.

But like all such bits of folksy advice, it's difficult to know when it applies. Sticking to the wrong methodology just because you fear it might be too late to make a change -- that's not a good idea either. There's wisdom in recognizing when you have made a wrong start, even if you are already halfway through the course.

There's a lot to be said for administration. A good administrator is a tremendous benefit to an organization. Administrators at their best can build structures where wonderful things happen, can reward people who do them, can obtain resources for them, can clarify procedures and expectations so that people know how to get things done, can provide evidence to demonstrate the wonderful things happening.

I know that I want to work for good administrators, and I know that I've been very fortunate to work for them and learn from them. (The bad ones have taught me some important lessons, too.) But at least where I am now, here at the halfway point, I want to get off the administrative horse.

It's carrying me farther away from teaching, farther away from being a productive scholar. What it's carrying me towards is something that needs to be done, but it's not something I need to do. As a person who likes to be in full control of everything, whether it's any of my business of not, recognizing the difference between "a job that needs to be done well" and "my job" has always been difficult for me. Here halfway through, I have to remind myself that caring about something does not require managing or leading it.

I've received a lot of great advice about this halfway point from relative strangers and from people who know me well. Most of it is simple and obvious, but rings almost heartbreakingly true. Just because you are good at something does not mean it's what you ought to do. You can't be there for the people you care about unless you take care of yourself. Arrange your life to spend the bulk of your time on what's most important.

It's been hard to accept the conclusions that are inescapable when I follow that advice, because I've spend so much time riding this horse to the middle of the stream. But it would be more foolish to stay on this horse than to attempt a change, however risky.

When I entered academia, I wanted to help students mature in their thinking about religion. I've done less and less of that each year. It's no less needed than fifteen years ago; quite the opposite. It would be a personal failure, and a terrible shame, if I let go of that goal when I have the ability and the position to accomplish it. And focusing on what's important to me will allow me to reclaim the energy that administrative tasks tend to drain away. The thought of doing more of the latter in the future is bleak and dispiriting; the thought of teaching the subjects about which I'm passionate, of reading, researching, and writing in the field where I can contribute something unique, is exciting. The message couldn't be more clear.

That's where I stand, halfway through. Changing horses and changing courses is a process. I'm not where I was in this process of rethinking and reorienting six months ago, but if you'd asked me then where I thought I was going, I should have told you, if I were being honest, that I suspected I might end up here. I might have feared it more than anticipated it then. Now the fear is diminishing.

Maybe I've been on the other horse for awhile, and just needed to open my eyes to see which way I've been headed. Check back in a few months and see if I've picked up the reins or have been swept away.

Labels:

administration,

midlife crisis,

personal history,

teaching

Sunday, June 9, 2013

No retreat, no surrender

Now it can be told. The new publishing venture that I mentioned in my last infrequent update, the one that Noel is helping to launch (and his first salaried, non-freelance job in decades) is The Dissolve, a new film site from Pitchfork Media. Right now they're just a placeholder site, a Tumblr, and a Twitter account, but the first real content will hit the streets next month. (And notice how cleverly I titled that last post, before the name of the site had officially been announced.)

Noel is energized and feeling creative, both doing administrative thinking like mapping out how the DVD reviews will be assigned and scheduled, and writing essays and reviews that will start appearing when the site goes live. It's a terrific place for him to be in his early forties: starting a new venture that builds on all the experience and expertise he's developed in the past twenty-odd years of critical writing.

And me? Well, I'm almost as happy as he is. Happier, maybe. I set out with some trepidation on my first research trip last month, to Hartford, Connecticut. This was the acid test. Could I find prayer shawl knitters to talk to? Would they want to talk to me, if I found them? Would my questions elicit the kinds of information I needed to know? I was elated by the result. I talked to 15 people in 8 interviews over the course of 6 full days in Hartford -- mostly in the surrounding area: Windsor, South Windsor, Farmington, Stafford Springs, Vernon. They were generous with their time and with their organizational energy, helping me get in touch with other members of their groups. And they seemed to appreciate the questions I asked, both the prosaic ones that allowed them to explain how their ministries worked, and the more unusual ones that asked them to reflect on what it means. I came home with about eleven and a half hours of interview recordings. And with some new ideas, too, about what themes might be present in this subject matter and in these women's experience that I hadn't hypothesized. That's how qualitative research is supposed to work; you continually reshape your hypothesis and redirect your investigation based on what you find as you explore. How relieved I am to find that it's happening here!

In a couple of weeks I head to Seattle for my second research trip, and my calendar for the six full days I'm there is already chock full of interviews. I'm trying to push myself to make maximum use of my time in the field, but I know now from experience that doing these interviews is hard work. I was glad in Hartford for some downtime, an empty morning or afternoon here and there (my evenings were almost all taken), to be alone and rest from the effort of connecting with other human beings. I was glad for flexibility in my driving schedule, so I could head out early if need be to avoid rush hour traffic and the frequent heavy rain that blanketed Connecticut while I was there. Knowing I was not so tightly scheduled was important for my peace of mind.

I've also used my freedom while on sabbatical to think about my mid-life crisis, to examine my reactions to this research activity and to being free of administrative duties, and have some preliminary thoughts about what I want the rest of my academic career to look like. Just preliminary; every time I follow them too far down the road to prospective action I get cold feet. But I'm remembering what led me into this life in the first place, and what fed my fire in those early years. I'm different now, but it's still useful to ask the question of what I would most regret not accomplishing twenty years in the future, based on what I wanted to do when I started out and what I've found that I have to offer along the way.

More to come, of course. Meanwhile. bookmark The Dissolve, and if you're in the Seattle area, let me know so we can cross paths while I'm there.

Noel is energized and feeling creative, both doing administrative thinking like mapping out how the DVD reviews will be assigned and scheduled, and writing essays and reviews that will start appearing when the site goes live. It's a terrific place for him to be in his early forties: starting a new venture that builds on all the experience and expertise he's developed in the past twenty-odd years of critical writing.

And me? Well, I'm almost as happy as he is. Happier, maybe. I set out with some trepidation on my first research trip last month, to Hartford, Connecticut. This was the acid test. Could I find prayer shawl knitters to talk to? Would they want to talk to me, if I found them? Would my questions elicit the kinds of information I needed to know? I was elated by the result. I talked to 15 people in 8 interviews over the course of 6 full days in Hartford -- mostly in the surrounding area: Windsor, South Windsor, Farmington, Stafford Springs, Vernon. They were generous with their time and with their organizational energy, helping me get in touch with other members of their groups. And they seemed to appreciate the questions I asked, both the prosaic ones that allowed them to explain how their ministries worked, and the more unusual ones that asked them to reflect on what it means. I came home with about eleven and a half hours of interview recordings. And with some new ideas, too, about what themes might be present in this subject matter and in these women's experience that I hadn't hypothesized. That's how qualitative research is supposed to work; you continually reshape your hypothesis and redirect your investigation based on what you find as you explore. How relieved I am to find that it's happening here!

In a couple of weeks I head to Seattle for my second research trip, and my calendar for the six full days I'm there is already chock full of interviews. I'm trying to push myself to make maximum use of my time in the field, but I know now from experience that doing these interviews is hard work. I was glad in Hartford for some downtime, an empty morning or afternoon here and there (my evenings were almost all taken), to be alone and rest from the effort of connecting with other human beings. I was glad for flexibility in my driving schedule, so I could head out early if need be to avoid rush hour traffic and the frequent heavy rain that blanketed Connecticut while I was there. Knowing I was not so tightly scheduled was important for my peace of mind.

I've also used my freedom while on sabbatical to think about my mid-life crisis, to examine my reactions to this research activity and to being free of administrative duties, and have some preliminary thoughts about what I want the rest of my academic career to look like. Just preliminary; every time I follow them too far down the road to prospective action I get cold feet. But I'm remembering what led me into this life in the first place, and what fed my fire in those early years. I'm different now, but it's still useful to ask the question of what I would most regret not accomplishing twenty years in the future, based on what I wanted to do when I started out and what I've found that I have to offer along the way.

More to come, of course. Meanwhile. bookmark The Dissolve, and if you're in the Seattle area, let me know so we can cross paths while I'm there.

Labels:

Noel,

research,

sabbatical,

summer,

The Dissolve,

writing

Sunday, May 12, 2013

Dissolve to next scene

Definition of infrequent posting: My last post was in late March, and announced my sabbatical for the summer (actually nearly a month after it was approved). This post, on Mother's Day 2013, contemplates the start of my sabbatical in just two days.

It seems like it's taken at least a full semester since spring break to get to this long-awaited point, even though it's only been seven weeks. April has been a month of intense hard work, with two major service projects in my two classes involving on-campus events coming to fruition. I ended the semester drained; the word that kept coming to mind, frankly, was "defeated." But at least it wasn't an ordinary summer stretching out in front of me. Wonderful as that can be to look forward to, it wasn't going to cut it in my burned-out state.

Because of my sabbatical, I won't be working on anything but my book after Tuesday. Well, I'll have to work on my promotion application, which has made almost no progress since spring break, and will be due shortly after I return from sabbatical. But nothing that has to do with my normal administrative duties. No freshman orientation. No information management. No reports. No strategic planning. No assessment. No curriculum development. No course prep. Nothing but reading, writing, interviewing, and organizing material for my prayer shawl ministry book.

It might sound like I'm already there. But this week, representing the transition from my administrative job to my sabbatical, involves several big tasks.

Here's my to-do list for Monday and Tuesday, my last days at work as associate dean:

- Complete sections of the annual report for which I'm responsible, chiefly reporting on the status of goals from the last year.

- List specifications for computer and A/V purchases for several classrooms, so that they can be ordered by the secretary.

- Brainstorm goals for the upcoming year with administrative team.

- Convert cash donations for service learning fundraisers into checks, write cover letters, and send to the appropriate charities.

And here's my to-do list for Wednesday through Friday, the first days of my sabbatical:

- Familiarize myself with my interview recording setup.

- Ascertain if I need any more equipment or backups.

- Conduct a trial run of my interview outline with a local subject.

- Schedule and confirm interviews in Hartford, Connecticut, where I'm headed next week.

- Make travel plans for my next trip in late June.

- Continue reading and notetaking from my growing stack of research texts.

Noel is in Chicago this upcoming week starting his new job (details on that forthcoming). It's hugely exciting for both of us to be opening the door to new lives in the same week. His change is more permanent; mine is more of an extended vacation from my usual routine. I'm as eager for him to get started as I am to start my own sabbatical. In his absence, I have a few additional items for the ol' to-do list, related to being sole custodial parent this week, including school chauffeuring duties that will shorten my office workdays by a couple of hours (making those Monday-Tuesday to-dos more difficult to achieve without taking work home).

I've been looking forward to this Wednesday, May 15, the first day of my sabbatical, for a long time. I'm nervous about being able to do what I'm setting out to do, and I'm aware that I'll be working just as hard and long on this (if not more so) as I do on my teaching and administrative work normally. I'm already stressing about squeezing all the pre-Hartford sabbatical tasks into just a few days this week before I hop on a plane next Monday.

But oh, the appeal, the longed-for luxury of turning my attention to Just One Thing rather than trying to squeeze my scholarly work and theological thinking into the odd half-hours left over after the million and one things of my normal job. Sabbatical, here I come.

Labels:

administration,

Noel,

prayer shawl ministry,

sabbatical,

travel,

writing

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Taking a break

It's spring break. More accurately, it's the last day of spring break. And it's been a fantastic experience. Every day I've been in the office, mostly all alone (on two days, two different co-workers were also present). Spring break is like a harbinger of summer, with its empty campus and long stretches of unallocated time.

And then the end of the semester rushes back, and it's five weeks of utter chaos before summer actually starts. Usually I think of that chaos as the last gasp of activity before a more leisurely pace for three months. But this year is different.

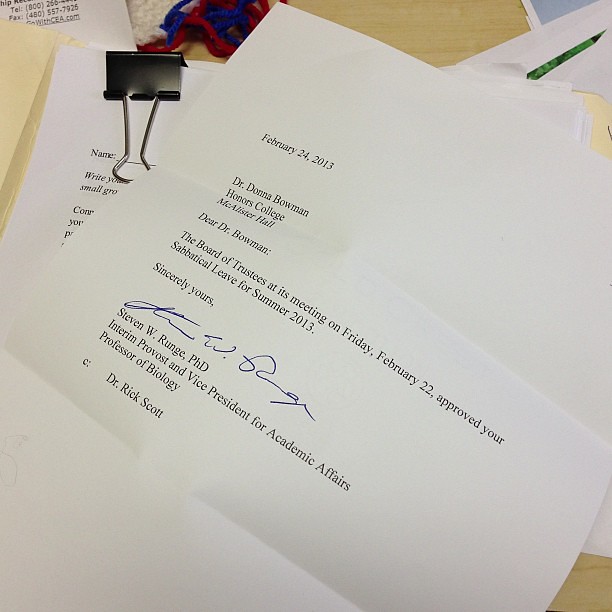

I applied for and received a sabbatical for the upcoming summer. Most sabbaticals are given for fall or spring semesters, because most faculty don't have regular duties in the summer for which they would need official release. But administrators, like me, can only be granted a sabbatical for the summer, because their administrative functions would (presumably) be more difficult to replace or reassign than the teaching duties of faculty in a normal semester.

This is the first sabbatical I've ever applied for. I'm in my twelfth year of teaching. Prior to a few years ago, when I considered a sabbatical, I didn't have a major project that warranted a request. But now I do -- a book about the theology of prayer shawl ministries, under contract and due next spring.

And the university and the publishing company aren't the only institutions expecting results from my summer off. I have a grant covering some of the travel I need to do for my research and even a course release to give me more time to write this fall. There are another couple of grants still in the pipeline, at least one of which I'm quite hopeful will be funded.

So my sabbatical will be far from relaxing. On the contrary, I'm hoping to travel fully a third of the time. But I'm still looking forward to it as a period of much-needed rest. While I'm not in active crisis like I was a few months ago, I'm still experiencing burnout in my job. I'm still feeling dread about the approaching pressure to step up in administration, and still wondering whether I should instead step aside.