That sense of retro robustness has characterized the last few days, actually, as I dived into the third Gasoline Alley collection from Drawn and Quarterly. I fell in love with Frank King's original strip when the sublimely beautiful first volume came out a couple of years ago. And ever since, I've been trying to figure out what it is about this 1920s comic strip that has such a hold over me.

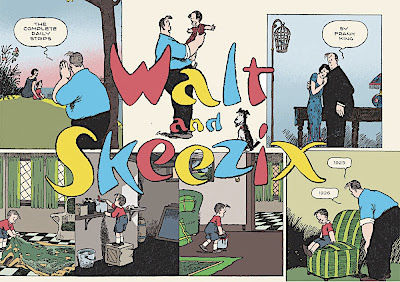

Walt and Skeezix: The Complete Daily Strips, 1925-1926 sees the alley bunch (a group of men who own garages and are always puttering around automobiles) go in together on a seaside hotel investment scheme; Skeezix, now four or five years old, in danger of once again being snatched by the haughty opera star Mme. Octave; and most notably, our hero Walt finally getting up enough pluck to propose to Phyllis Blossom. It's Walt who carries the emotional load of the comic. A broadly drawn fat man with a tiny pin head and an open-book face, he's transparently anxious, joyful, and wistful by turns as he takes care of the orphan Skeezix who was left on his doorstep as a baby. Skeezik's trusting, uncomplicated expressions -- often communicated through the limp arch of his little body slung over Walt's broad shoulder -- offer a poignant counterpart to Walt's clumsy but well-meaning efforts at parenting.

The result is about as far from our stereotype of simplistic, crude, overstylized, or self-consciously artistic early strips as can be imagined. Gasoline Alley occupies a crucial niche in the history of the powerful, compact comic strip that would peak in the 1960s with Peanuts.

More than a historical curiosity, though, these visions of men, women, children, technology, money, and relationships from the twenties tug at my heart and imagination. I worry about Walt, enjoy Skeezik's altogether boyish play, fume a little at the way Phyllis plays with Walt's affections, and get frustrated at the secrets she and Mme. Octave keep from Walt and reader alike. Even the supporting cast, much more like the broad types that we expect to populate strips of the time, have wormed their way into my affection; Avery, the skinflint who nevertheless falls for every crazy snake oil salesman who walks down the alley, makes me laugh out loud. In five cumulatively absurd panels, King can send him halfway around the county to get ten cents he's owed, spending ten dollars in the process.

I'm sure that it's no accident I fell in love with Gasoline Alley when my own children were small. But there's also the timing of the publishing projects that are bringing these pieces of history into the twenty-first century. There is something larger than me and my personal obsessions to Gasoline Alley's hold on my affections. It's emblematic of an appreciation of the past's complexity -- not just our debt to it in the creative accomplishments it made possible, but also the unique value and integrity of the moment itself. It's a kind of miracle, a quirk of historical eras, that we can connect to the world of eighty years ago through these pen and ink lines.

I assume that we're living near the end of our historical epoch, the Industrial Age, the Technological Age, the Age of the Internal Combustion Engine. At some point the paradigm will change -- and both Walt's 1925 alley and our 2007 subdivision will seem equally as far away to the denizens of the next world as the American Revolution and the Civil War, those bookends of American pastoralism, seem equally far away to us.

No comments:

Post a Comment